![]() Mój ‘Ojczulek’ Dariusz Wąsowicz ( 1910-1973) – Nazywaliśmy go tak według rodzinnej tradycji, jaką wyniósł z domu, bo i on nazywał Ojczulkiem swego ojca Rafała Wąsowicza.

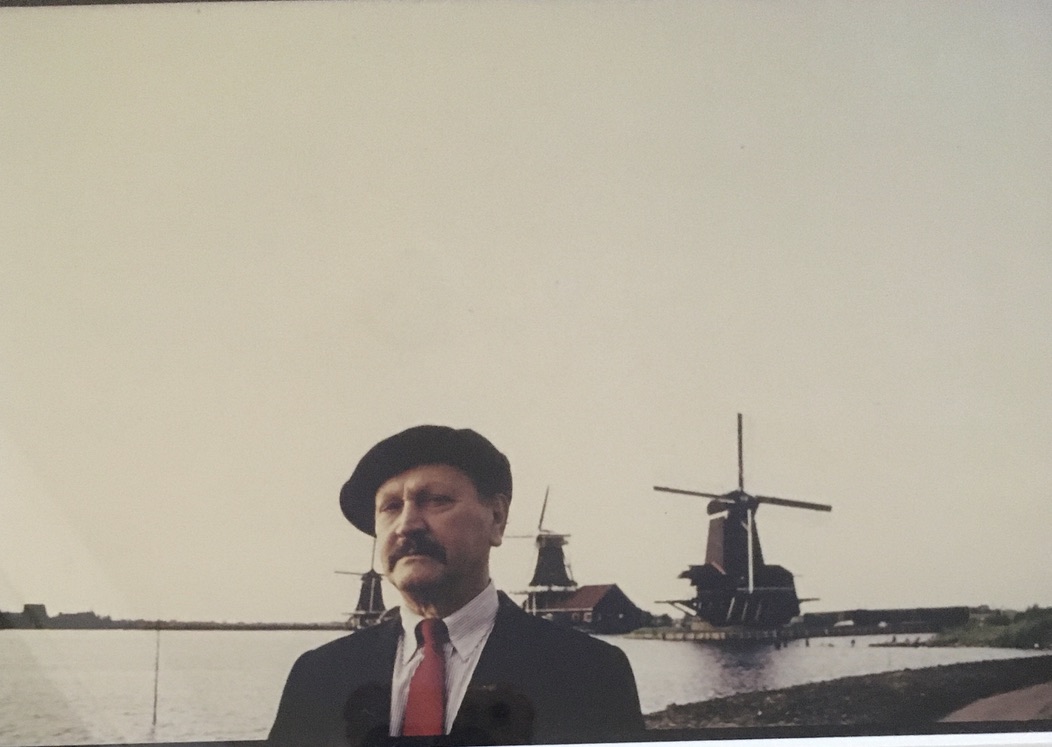

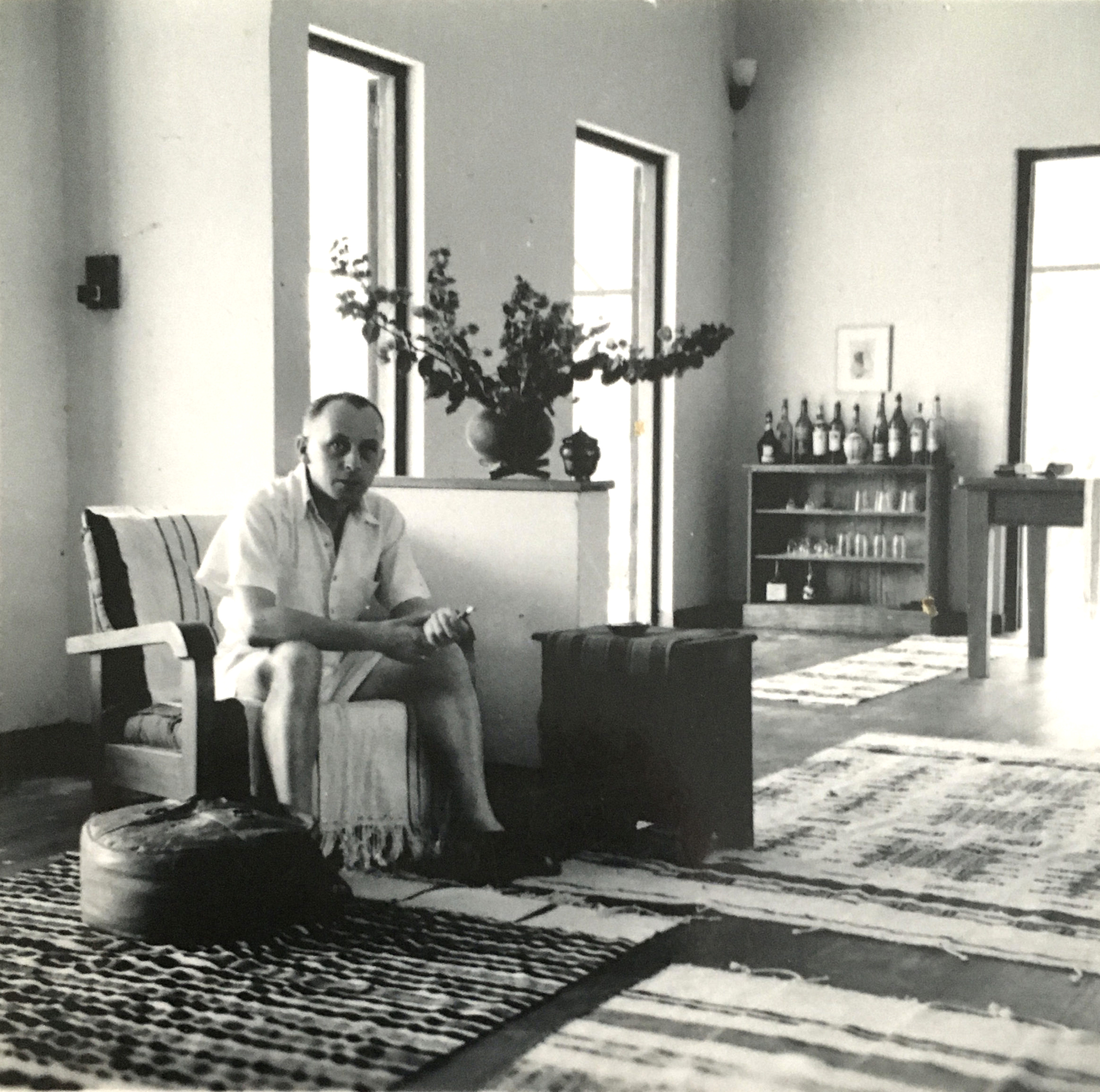

Mój ‘Ojczulek’ Dariusz Wąsowicz ( 1910-1973) – Nazywaliśmy go tak według rodzinnej tradycji, jaką wyniósł z domu, bo i on nazywał Ojczulkiem swego ojca Rafała Wąsowicza.

![]() My Father ‘Ojczulek’ Dariusz Wąsowicz ( 1910-1973) – We used to call him ’Ojczulek’ according to the family tradition that he brought out of the home, because he also called his father Rafał Wąsowicz a ’Ojczulek’.

My Father ‘Ojczulek’ Dariusz Wąsowicz ( 1910-1973) – We used to call him ’Ojczulek’ according to the family tradition that he brought out of the home, because he also called his father Rafał Wąsowicz a ’Ojczulek’.

![]() Mon père ‘Ojczulek’ Dariusz Wąsowicz ( 1910-1973 ) – On l’appelait ainsi selon la tradition familiale qu’il gardait de la maison, car il appelait aussi son père Rafał Wąsowicz un ‘Ojczulek’.

Mon père ‘Ojczulek’ Dariusz Wąsowicz ( 1910-1973 ) – On l’appelait ainsi selon la tradition familiale qu’il gardait de la maison, car il appelait aussi son père Rafał Wąsowicz un ‘Ojczulek’.

![]() Mijn Vader ‘Ojczulek’ Dariusz Wąsowicz ( 1910-1973) – We noemden hem ‘Ojczulek’ volgens de familietraditie die hij uit de familietraditie bracht, omdat ook hij noemde zijn vader Rafał Wąsowicz een ‘Ojczulek”.

Mijn Vader ‘Ojczulek’ Dariusz Wąsowicz ( 1910-1973) – We noemden hem ‘Ojczulek’ volgens de familietraditie die hij uit de familietraditie bracht, omdat ook hij noemde zijn vader Rafał Wąsowicz een ‘Ojczulek”.

![]() Zaczęłam malować ten portret latem 1972, jako podwójny potret moich rodziców, Ojczulka i Sabinki, w czase ich pobytu w Amsterdamie. Sabinka śmiejąc się ostrzegła mnie, że jest niemożliwa do namalowania, opowiadając anegdotę o cioci Maryli, która próbowała namalować jej portret, ale zrezygnowała mówiąc, że Sabinka jest niemożliwym modelem i nie da się uchwycić w farbie. (Maryla była świetną malarką). Pomyślałam sobie, ‘zobaczymy’ i zrobiłam pierwszy szkic obu głów. Plan wyglądał dobrze, więc zaczęłam malować. Ojczulek pojawił się na płótnie szybko i ku ogólnemu zadowoleniu, Sabinka jednak wymagala większego wysiłku, ale nie dawałam za wygraną i malowałam dalej próbując uchwycić żywe podobieństwo. Lato minęło i Ojczulek i Sabinka wrócili do Warszawy a nieskończony obraz zatrzymałam w Amsterdamie z nadzieją wykończenia go później. Ojczulek zmarł 14 marca 1973. Na życzenie Sabinki podzieliłam płótno na dwoje aby jedynie portret Ojczulka oprawić w czarna ramę i tak wisi do dziś na ścianie w Warszawskim mieszkanu.

Zaczęłam malować ten portret latem 1972, jako podwójny potret moich rodziców, Ojczulka i Sabinki, w czase ich pobytu w Amsterdamie. Sabinka śmiejąc się ostrzegła mnie, że jest niemożliwa do namalowania, opowiadając anegdotę o cioci Maryli, która próbowała namalować jej portret, ale zrezygnowała mówiąc, że Sabinka jest niemożliwym modelem i nie da się uchwycić w farbie. (Maryla była świetną malarką). Pomyślałam sobie, ‘zobaczymy’ i zrobiłam pierwszy szkic obu głów. Plan wyglądał dobrze, więc zaczęłam malować. Ojczulek pojawił się na płótnie szybko i ku ogólnemu zadowoleniu, Sabinka jednak wymagala większego wysiłku, ale nie dawałam za wygraną i malowałam dalej próbując uchwycić żywe podobieństwo. Lato minęło i Ojczulek i Sabinka wrócili do Warszawy a nieskończony obraz zatrzymałam w Amsterdamie z nadzieją wykończenia go później. Ojczulek zmarł 14 marca 1973. Na życzenie Sabinki podzieliłam płótno na dwoje aby jedynie portret Ojczulka oprawić w czarna ramę i tak wisi do dziś na ścianie w Warszawskim mieszkanu.

![]() I started painting this portrait in the summer of 1972 initially as a ‘double portrait’ of my parents Ojczulek and Sabinka together, during their stay in Amsterdam. Sabinka warned me, laughing, saying that she is impossible to portrait and told me an anecdote aunt Maryla, Ojczulek’s sister, who attempted to paint Sabinka’s portrait, but gave up saying that Sabinka was a too difficult model to grasp in paint. (Aunt Maryla was a great artist!) I thought to myself ‘well we’ll see’ and started by sketching the two heads and placing them on the canvas. The plan looked promising so I started painting! Ojczulek appeared on the canvas in no time and to mutual satisfaction. Sabinka’s portrait, frustrating enough, required more effort, but I didn’t give up and continued to paint trying to grasp the true resemblance. After the summer Ojczulek and Sabinka returned to Warsaw and I kept the unfinished painting in Amsterdam to hopefully, finish it later. Ojczulek died on 14th march 1973. Following Sabinka’s wish I divided the canvas in two to fit only Ojczulek’s portrait into the black frame and it has been hanging in the Warsaw appartement since.

I started painting this portrait in the summer of 1972 initially as a ‘double portrait’ of my parents Ojczulek and Sabinka together, during their stay in Amsterdam. Sabinka warned me, laughing, saying that she is impossible to portrait and told me an anecdote aunt Maryla, Ojczulek’s sister, who attempted to paint Sabinka’s portrait, but gave up saying that Sabinka was a too difficult model to grasp in paint. (Aunt Maryla was a great artist!) I thought to myself ‘well we’ll see’ and started by sketching the two heads and placing them on the canvas. The plan looked promising so I started painting! Ojczulek appeared on the canvas in no time and to mutual satisfaction. Sabinka’s portrait, frustrating enough, required more effort, but I didn’t give up and continued to paint trying to grasp the true resemblance. After the summer Ojczulek and Sabinka returned to Warsaw and I kept the unfinished painting in Amsterdam to hopefully, finish it later. Ojczulek died on 14th march 1973. Following Sabinka’s wish I divided the canvas in two to fit only Ojczulek’s portrait into the black frame and it has been hanging in the Warsaw appartement since.

![]() J’ai commencé à peindre ce portrait à l’été 1972, comme un double portrait de mes parents, Ojczulek et Sabinka, lors de leur séjour à Amsterdam. Sabinka, en riant, m’a averti qu’elle était impossible de peindre, en racontant une anecdote sur tante Maryla qui a essayé de peindre son portrait, mais a renoncé disant que Sabinka était un modèle impossible et ne pouvait pas être capturé dans la peinture. (Maryla était une grande peintre). Je me suis dit ‘on verra’ et j’ai fait le premier croquis des deux têtes. Le plan avait l’air bien alors j’ai commencé à peindre. Ojczulek est apparu rapidement sur la toile et à la satisfaction générale, Sabinka, cependant a demandé plus d’efforts, mais je n’ai pas capitulé et j’ai continué à peindre, essayant de capturer la ressemblance vivante. L’été est passé et Ojczulek et Sabinka sont retournés à Varsovie et j’ai gardé la peinture inachevé à Amsterdam, dans l’espoir de la terminer plus tard. Ojczulek est mort le 14 mars 1973. A la demande de Sabinka, j’ai divisé la toile en deux pour que seul le portrait de papa rentre dans le cadre noir et depuis il pend toujours accroché au mur de l’appartement de Varsovie.

J’ai commencé à peindre ce portrait à l’été 1972, comme un double portrait de mes parents, Ojczulek et Sabinka, lors de leur séjour à Amsterdam. Sabinka, en riant, m’a averti qu’elle était impossible de peindre, en racontant une anecdote sur tante Maryla qui a essayé de peindre son portrait, mais a renoncé disant que Sabinka était un modèle impossible et ne pouvait pas être capturé dans la peinture. (Maryla était une grande peintre). Je me suis dit ‘on verra’ et j’ai fait le premier croquis des deux têtes. Le plan avait l’air bien alors j’ai commencé à peindre. Ojczulek est apparu rapidement sur la toile et à la satisfaction générale, Sabinka, cependant a demandé plus d’efforts, mais je n’ai pas capitulé et j’ai continué à peindre, essayant de capturer la ressemblance vivante. L’été est passé et Ojczulek et Sabinka sont retournés à Varsovie et j’ai gardé la peinture inachevé à Amsterdam, dans l’espoir de la terminer plus tard. Ojczulek est mort le 14 mars 1973. A la demande de Sabinka, j’ai divisé la toile en deux pour que seul le portrait de papa rentre dans le cadre noir et depuis il pend toujours accroché au mur de l’appartement de Varsovie.

![]() In de zomer van 1972 begon ik dit portret te schilderen als een dubbelportret van mijn beide ouders Ojczulek en Sabinka, tijdens hun verblijf in Amsterdam. Sabinka lachte en waarschuwde mij dat zij onmogelijk te portretteren is, en vertelde een anecdote over tante Maryla, die probeerde Sabinka te portretteren, maar gaf het op zeggend dat Sabinka een onmogelijke model was om in verf vangen. (Tante Maryla was een voortreffelijke schilderes). Ik dacht in mijzelf ‘we zien wel’ en begon met schetsen van de twee hoofden op het doek. Het plan zag er goed uit dus ik begon te schilderen. Ojczulek verscheen op het doek snel en tot algemeen tevredenheid, Sabinka echter vereiste meer inspanning, maar ik gaf niet op en schilderde door zoekend naar de ware gelijkenis. Na de zomer keerden Ojczulek met Sabina terug naar Warschau en ik bewaarde het onvoltooide schilderij om er aan door te werken. Ojczulek stierf op 14 maart 1973. Op Sabinka’s verzoek heb ik het doek in tweeën verdeeld om alleen Ojczulek’s portret in het zwarte lijst te passen en zo hangt hij tot vandaag in het Warschause appartement.

In de zomer van 1972 begon ik dit portret te schilderen als een dubbelportret van mijn beide ouders Ojczulek en Sabinka, tijdens hun verblijf in Amsterdam. Sabinka lachte en waarschuwde mij dat zij onmogelijk te portretteren is, en vertelde een anecdote over tante Maryla, die probeerde Sabinka te portretteren, maar gaf het op zeggend dat Sabinka een onmogelijke model was om in verf vangen. (Tante Maryla was een voortreffelijke schilderes). Ik dacht in mijzelf ‘we zien wel’ en begon met schetsen van de twee hoofden op het doek. Het plan zag er goed uit dus ik begon te schilderen. Ojczulek verscheen op het doek snel en tot algemeen tevredenheid, Sabinka echter vereiste meer inspanning, maar ik gaf niet op en schilderde door zoekend naar de ware gelijkenis. Na de zomer keerden Ojczulek met Sabina terug naar Warschau en ik bewaarde het onvoltooide schilderij om er aan door te werken. Ojczulek stierf op 14 maart 1973. Op Sabinka’s verzoek heb ik het doek in tweeën verdeeld om alleen Ojczulek’s portret in het zwarte lijst te passen en zo hangt hij tot vandaag in het Warschause appartement.

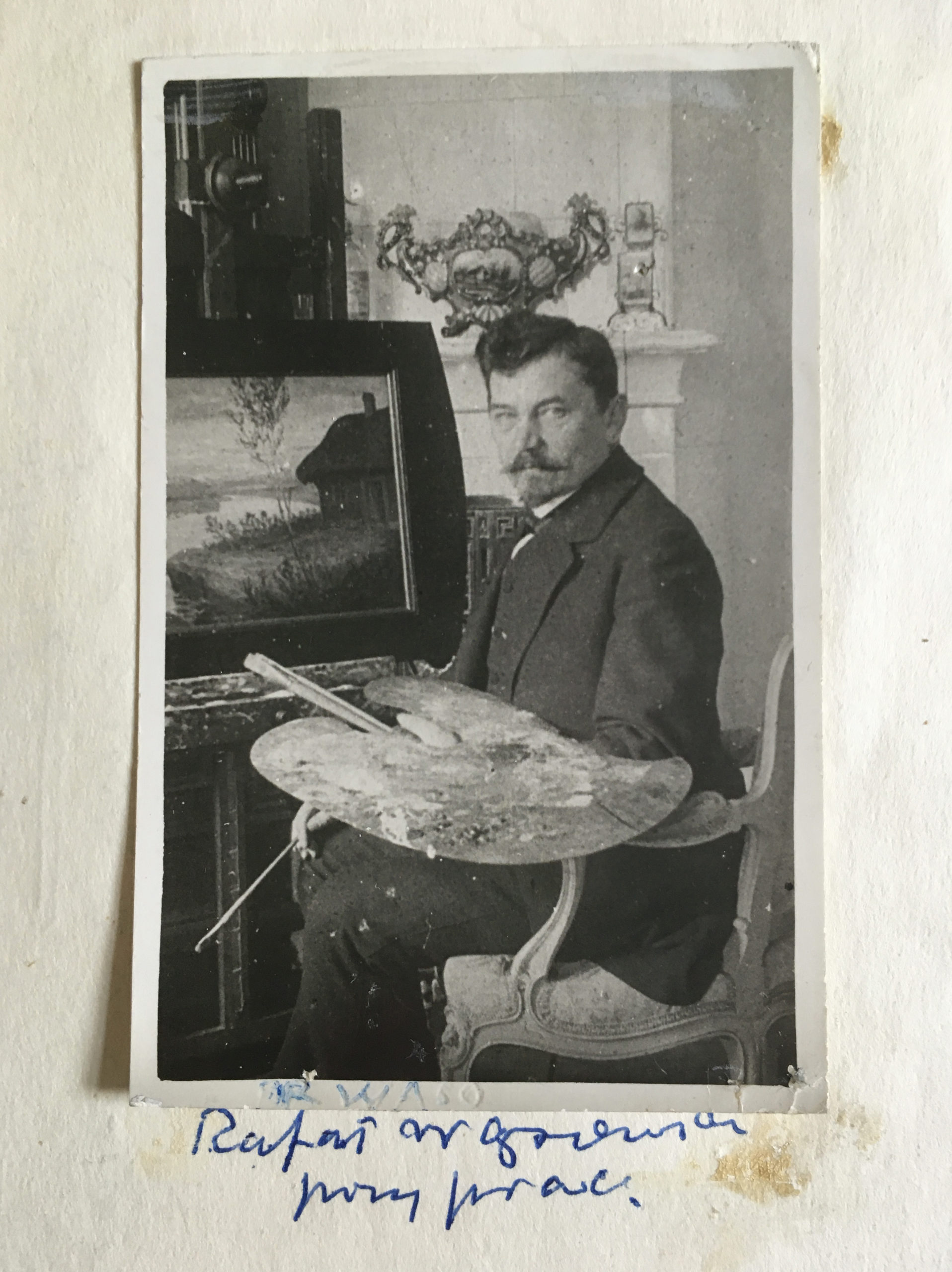

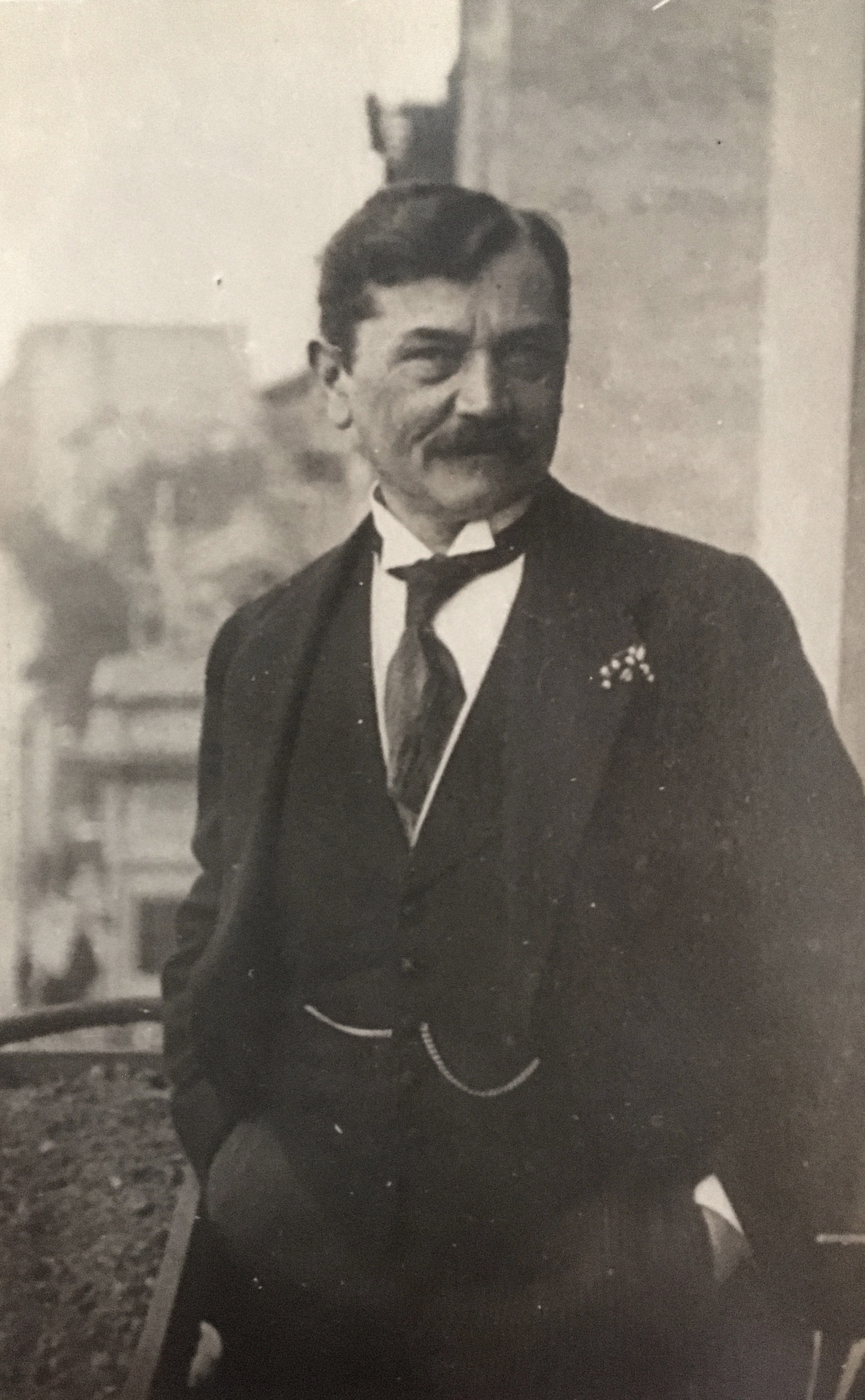

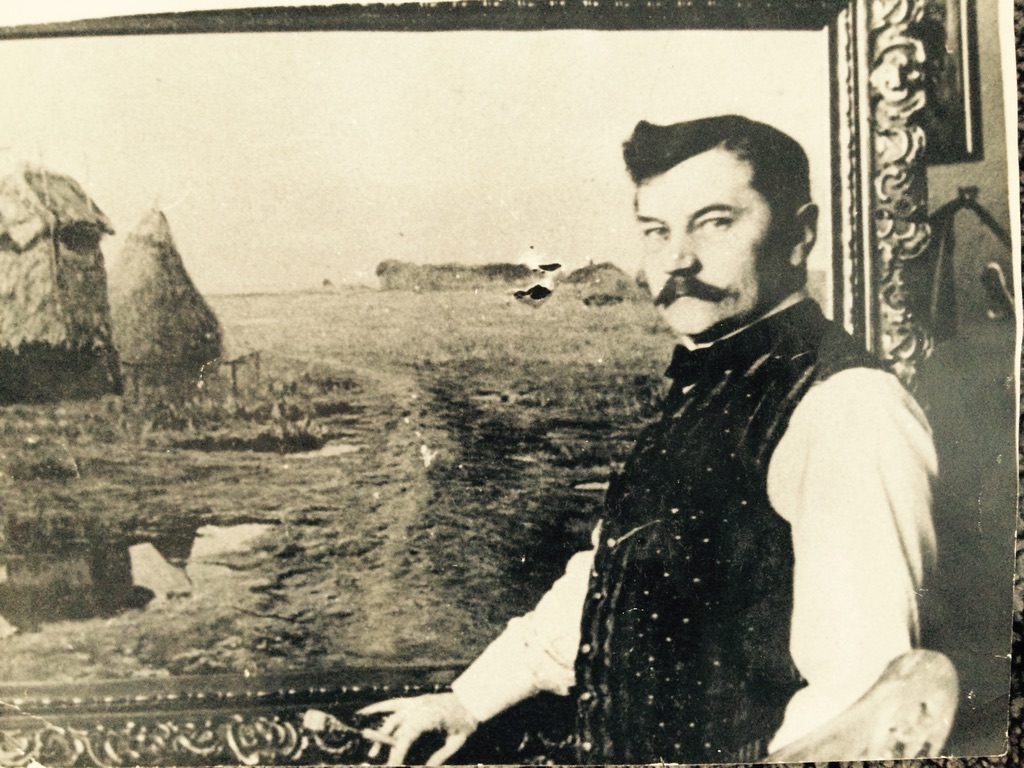

[pl] Mój dziadek Rafał Wąsowicz artysta malarz. Kilka z niewielu zachowanych zdjęć mojego dziadka.

[eng] My grandfather Rafał Wąsowicz – artist-painter. Some of the few preserved photographs of my grandfather.

[fr] Mon grand-père Rafał Wąsowicz artiste-peintre. Quelqes des rares photographies conservées de mon grand-père.

[nl] Mijn grootvader Rafał Wąsowicz – kunstschilder. Enkele van de weinige bewaarde foto’s van mijn grootvader.

![]() Dziadka Rafała nie znałam bo zginął z rąk hitlerowskich oprawców w czasie Powstania Warszawskiego. Po zniszczeniu Warszawy niewiele zachowało się z jego dorobku artystycznego, ale ostatnio coraz częściej pojawiają się jego obrazy na różnych aukcjach sztuki.

Dziadka Rafała nie znałam bo zginął z rąk hitlerowskich oprawców w czasie Powstania Warszawskiego. Po zniszczeniu Warszawy niewiele zachowało się z jego dorobku artystycznego, ale ostatnio coraz częściej pojawiają się jego obrazy na różnych aukcjach sztuki.

![]() I didn’t know grandfather Rafal because he died, at the hands of the Nazi oppressors during Hitlers revenge for the Warsaw Uprising in august 1944. After the destruction of Warsaw, not much of his artistic heritage has been preserved, but recently his paintings have appeared more and more often at various art auctions.

I didn’t know grandfather Rafal because he died, at the hands of the Nazi oppressors during Hitlers revenge for the Warsaw Uprising in august 1944. After the destruction of Warsaw, not much of his artistic heritage has been preserved, but recently his paintings have appeared more and more often at various art auctions.

![]() Je n’ai pas connu mon grand-père Rafał car il est mort aux mains des oppresseurs nazis pendant l’Insurrection de Varsovie en 1944. Après la destruction de Varsovie, peu de sa production artistique a été conservée, mais récemment, ses peintures ont été de plus en plus souvent présentées dans diverses ventes aux enchères.

Je n’ai pas connu mon grand-père Rafał car il est mort aux mains des oppresseurs nazis pendant l’Insurrection de Varsovie en 1944. Après la destruction de Varsovie, peu de sa production artistique a été conservée, mais récemment, ses peintures ont été de plus en plus souvent présentées dans diverses ventes aux enchères.

![]() Ik kende grootvader Rafał niet omdat hij stierf vermoord door de nazi-beulen tijdens Hitlers wraak op de augustus 1944 opstand van Warschau. Na de verwoesting van Warschau is er niet veel van Rafał’s artistieke oeuvre bewaard gebleven, maar de laatste tijd verschijnen zijn schilderijen steeds vaker op verschillende kunstveilingen.

Ik kende grootvader Rafał niet omdat hij stierf vermoord door de nazi-beulen tijdens Hitlers wraak op de augustus 1944 opstand van Warschau. Na de verwoesting van Warschau is er niet veel van Rafał’s artistieke oeuvre bewaard gebleven, maar de laatste tijd verschijnen zijn schilderijen steeds vaker op verschillende kunstveilingen.

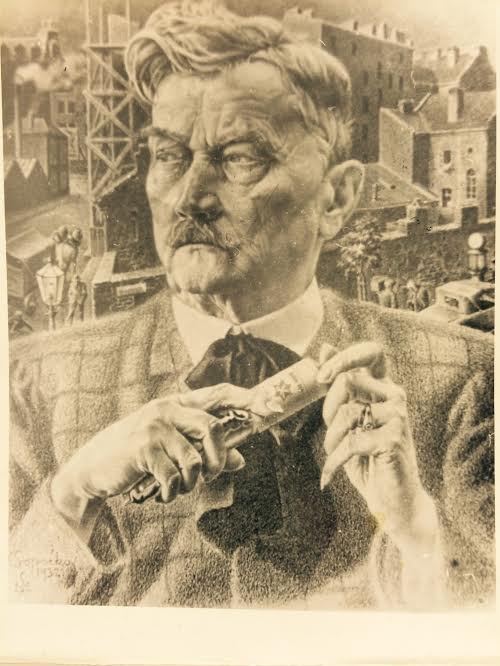

[pl] Portret Rafała Wąsowicza wykonany techniką litografii w 1932 roku przez jego zięcia grafika, ilustratora Konstantego Sopoćko na 65 lecie jego teścia Rafała. Wszystkie obiekty w tle ilustrują rozmaite przedsięwzięcia Rafała, też tuba, którą trzyma w ręku była wyrobem fabryki farb olejnych jego firmy.

[eng] Portrait of Rafał Wąsowicz made in the lithography-technique in 1932 by his son-in-law, graphic artist, illustrator Konstanty Sopoćko on the occasion of the 65th anniversary of his father-in-law Rafał. All the objects in the background illustrate Rafał’s various undertakings, also the tube of paint he is holding in his hand was a product of his enterprise.

[fr] Portrait de Rafał Wąsowicz réalisé avec la technique de lithographie en 1932 par son beau-fils, le graphiste, illustrateur Konstanty Sopoćko à l’occasion du 65ème anniversaire de son beau-père Rafał. Tous les objets en arrière-plan illustrent les différentes entreprises de Rafał. De plus, le tube qu’il tient à la main est un produit de l’usine de peinture à l’huile de sa société.

[nl] Portret van Rafał Wąsowicz uitgevoerd in de lithografietechniek in 1932 door zijn schoonzoon, graficus, illustrator Konstanty Sopoćko ter gelengenheid van de 65ste verjaardag van zijn schoonvader Rafał. Alle objecten in de achtergrond illustreren de verschillende ondernemingen van Rafał, ook de verftube die hij in zijn hand houdt was een product van zijn bedrijf.

1946

‘Maryla’ – Maria Wasoiwicz-Sopocko

1974

1976

![]() Moja ciocia Maria Wąsowicz-Sopoćko cudem przeżyła Powstanie Warszawskie tracąc w nim 13 letniego syna Krzysztofa Sopoćko. Była świetną akwarelistką i po wojnie do sędziwego wieku działała w Warszawie jako pedagog sztuki.

Moja ciocia Maria Wąsowicz-Sopoćko cudem przeżyła Powstanie Warszawskie tracąc w nim 13 letniego syna Krzysztofa Sopoćko. Była świetną akwarelistką i po wojnie do sędziwego wieku działała w Warszawie jako pedagog sztuki.

![]() My aunt Maria Wąsowicz-Sopoćko miraculously survived the Warsaw Uprising losing her 13-year-old son Krzysztof Sopoćko in it. She was an excellent watercolorist and after the war she worked in Warsaw as an art teacher until advanced age.

My aunt Maria Wąsowicz-Sopoćko miraculously survived the Warsaw Uprising losing her 13-year-old son Krzysztof Sopoćko in it. She was an excellent watercolorist and after the war she worked in Warsaw as an art teacher until advanced age.

![]() Ma tante Maria Wąsowicz-Sopoćko a miraculeusement survécu l’Insurrection de Varsovie, y perdant son fils de 13 ans Krzysztof Sopoćko. Elle était une excellente aquarelliste et après la guerre, elle a travaillé à Varsovie comme professeur d’art jusqu’à un âge avancé.

Ma tante Maria Wąsowicz-Sopoćko a miraculeusement survécu l’Insurrection de Varsovie, y perdant son fils de 13 ans Krzysztof Sopoćko. Elle était une excellente aquarelliste et après la guerre, elle a travaillé à Varsovie comme professeur d’art jusqu’à un âge avancé.

![]() Mijn tante Maria Wąsowicz-Sopoćko overleefde op miraculeuze wijze de opstand van Warschau waarbij ze haar 13-jarige zoon Krzysztof Sopoćko verloor. Ze was een uitstekende aquarelliste en werkte na de oorlog in Warschau als kunstdocent tot op zeer hoge leeftijd.

Mijn tante Maria Wąsowicz-Sopoćko overleefde op miraculeuze wijze de opstand van Warschau waarbij ze haar 13-jarige zoon Krzysztof Sopoćko verloor. Ze was een uitstekende aquarelliste en werkte na de oorlog in Warschau als kunstdocent tot op zeer hoge leeftijd.

[pl] Maria Wąsowicz-Sopoćko Akwarele z serii “Malowniczość polskiego stroju ludowego”.

[eng] Maria Wąsowicz-Sopoćko Aquarel series “Picturesque Polish folk costumes”.

[fr] Maria Wąsowicz-Sopoćko Aquarels de la série “Costumes folkloriques polonais pittoresques”.

[nl] Maria Wąsowicz-Sopoćko – Aquarellen uit de serie “Schilderachtige Poolse volkskostuums”.

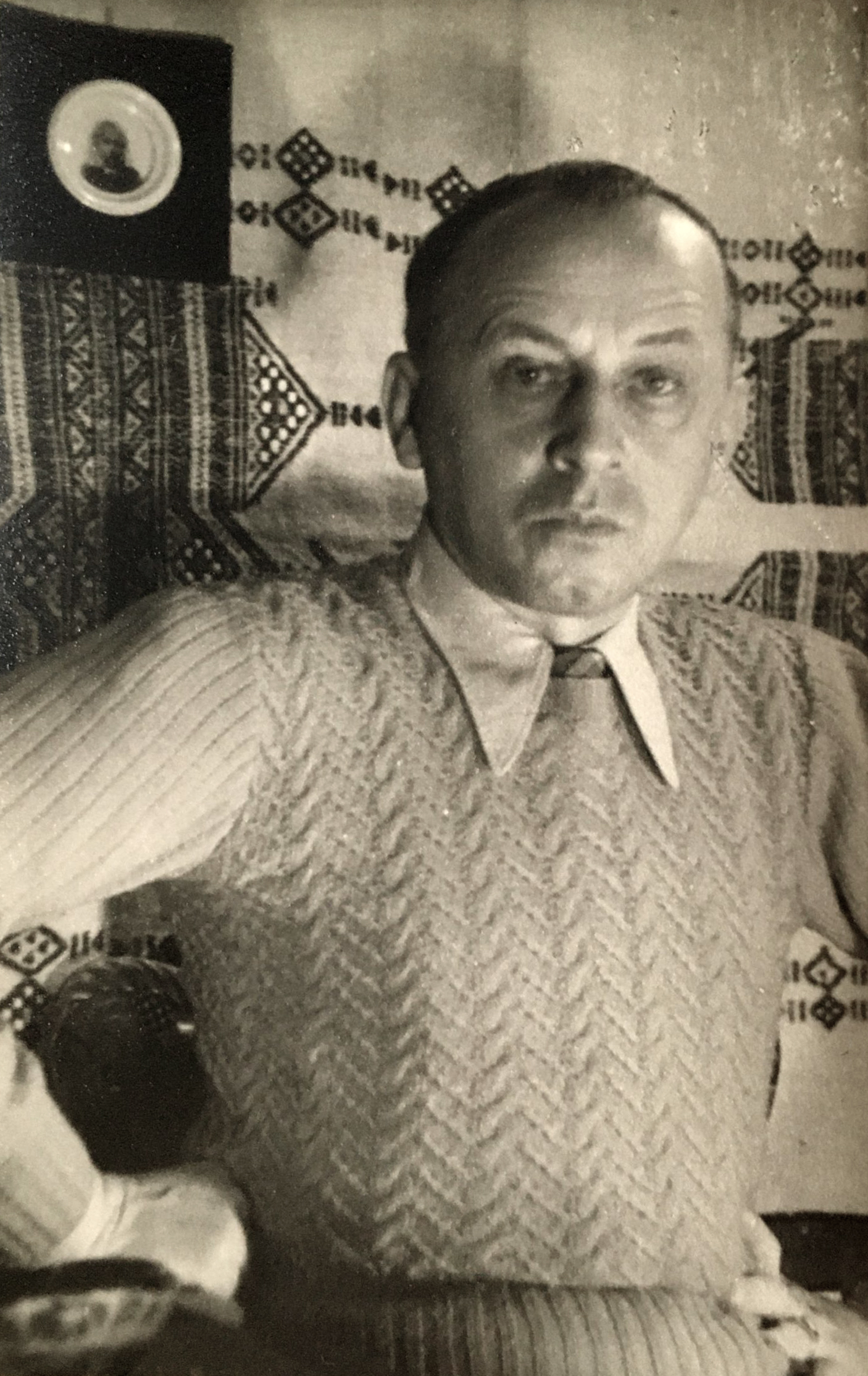

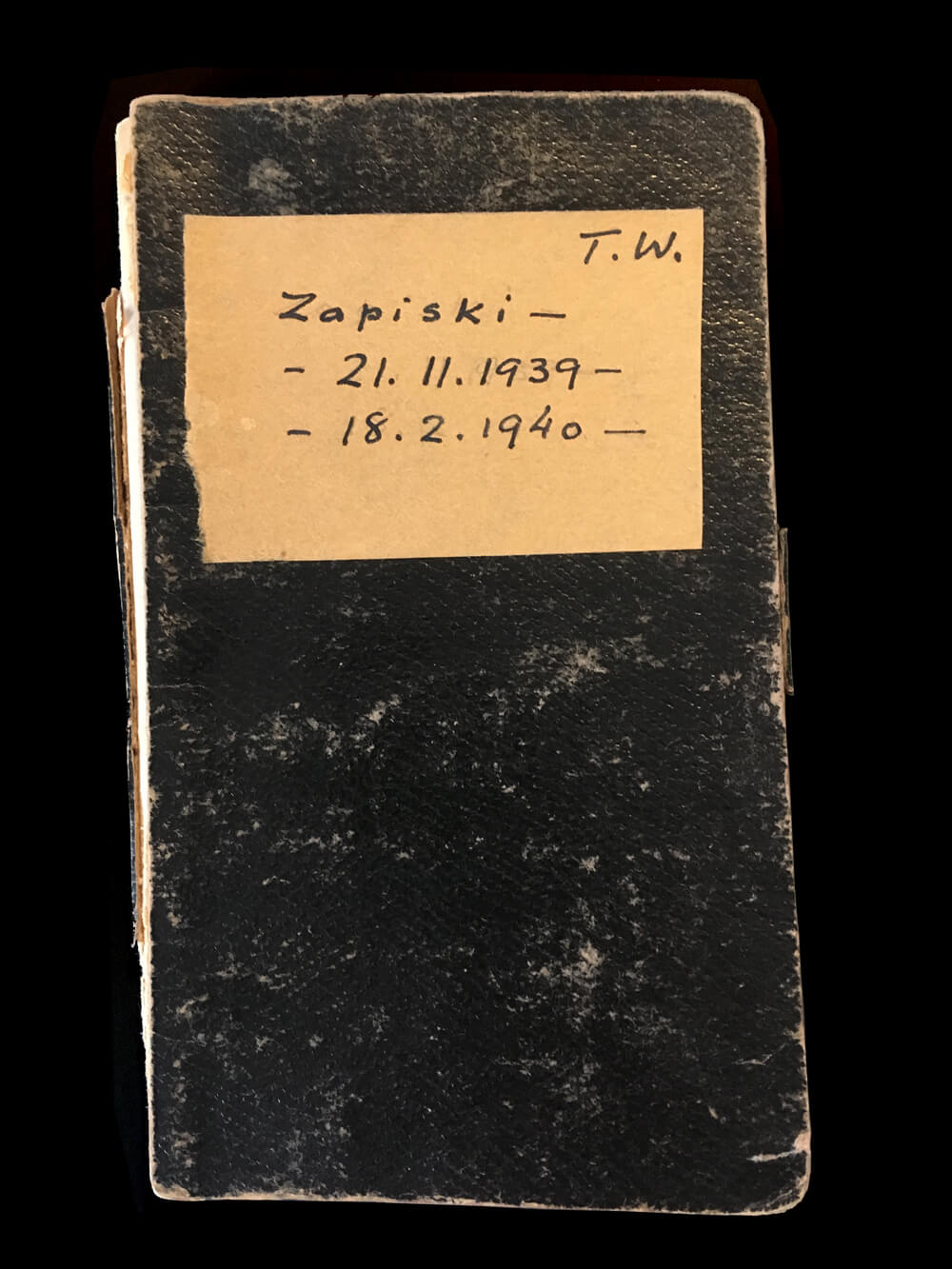

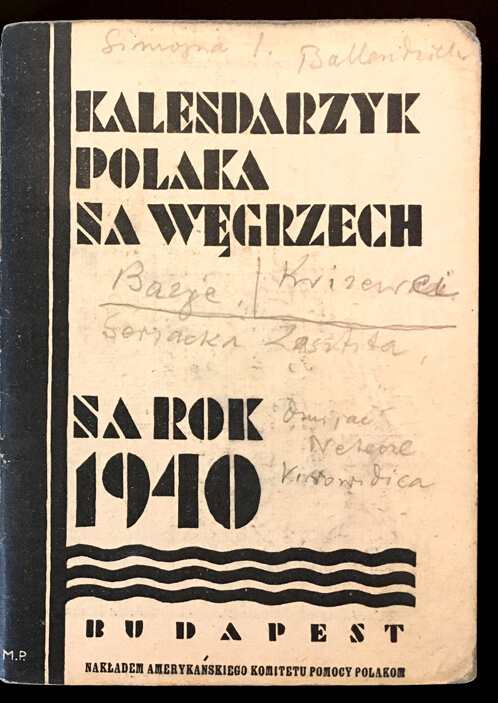

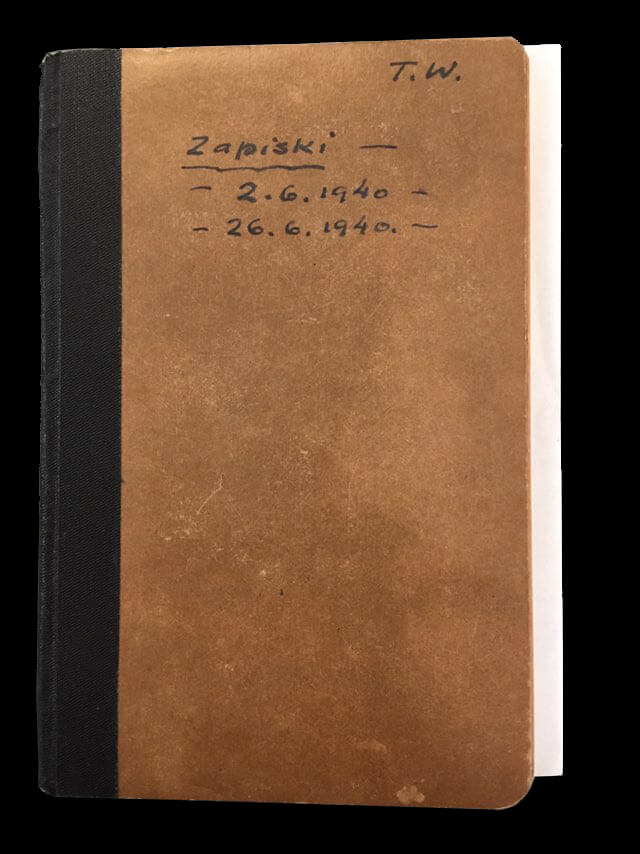

![]() Mój stryjek Tadeusz Wąsowicz, dr Edafologii po SGGW, w listopadzie 1939 po kapitulacji opuścił Polskę, aby uniknąć internowania przez okupanta. Ma wtedy 36 lat i od momentu opuszczenia domu rodzinnego w Warszawie prowadzi skrupulatnie pamiętnik. Dzięki pomocy zaprzyjaźnionych górali przedostał się przez Tatry na południe i po długiej wędrówce – przez Słowację, Węgry i Jugosławię dołączył do wojsk polskich we Francji. Koniec wojny zastał go wraz z wojskiem Polskim w Szkocji. Po wojnie Tadeusz, w rozterce jak wielu Polaków, pozostał w Anglii gdzie pracował jako naukowiec, wykładał w London Borough Politechnic i w Imperial College of Agriculture w Londynie gdzie zmarł w 1967 roku w wieku 63 lat.

Mój stryjek Tadeusz Wąsowicz, dr Edafologii po SGGW, w listopadzie 1939 po kapitulacji opuścił Polskę, aby uniknąć internowania przez okupanta. Ma wtedy 36 lat i od momentu opuszczenia domu rodzinnego w Warszawie prowadzi skrupulatnie pamiętnik. Dzięki pomocy zaprzyjaźnionych górali przedostał się przez Tatry na południe i po długiej wędrówce – przez Słowację, Węgry i Jugosławię dołączył do wojsk polskich we Francji. Koniec wojny zastał go wraz z wojskiem Polskim w Szkocji. Po wojnie Tadeusz, w rozterce jak wielu Polaków, pozostał w Anglii gdzie pracował jako naukowiec, wykładał w London Borough Politechnic i w Imperial College of Agriculture w Londynie gdzie zmarł w 1967 roku w wieku 63 lat.

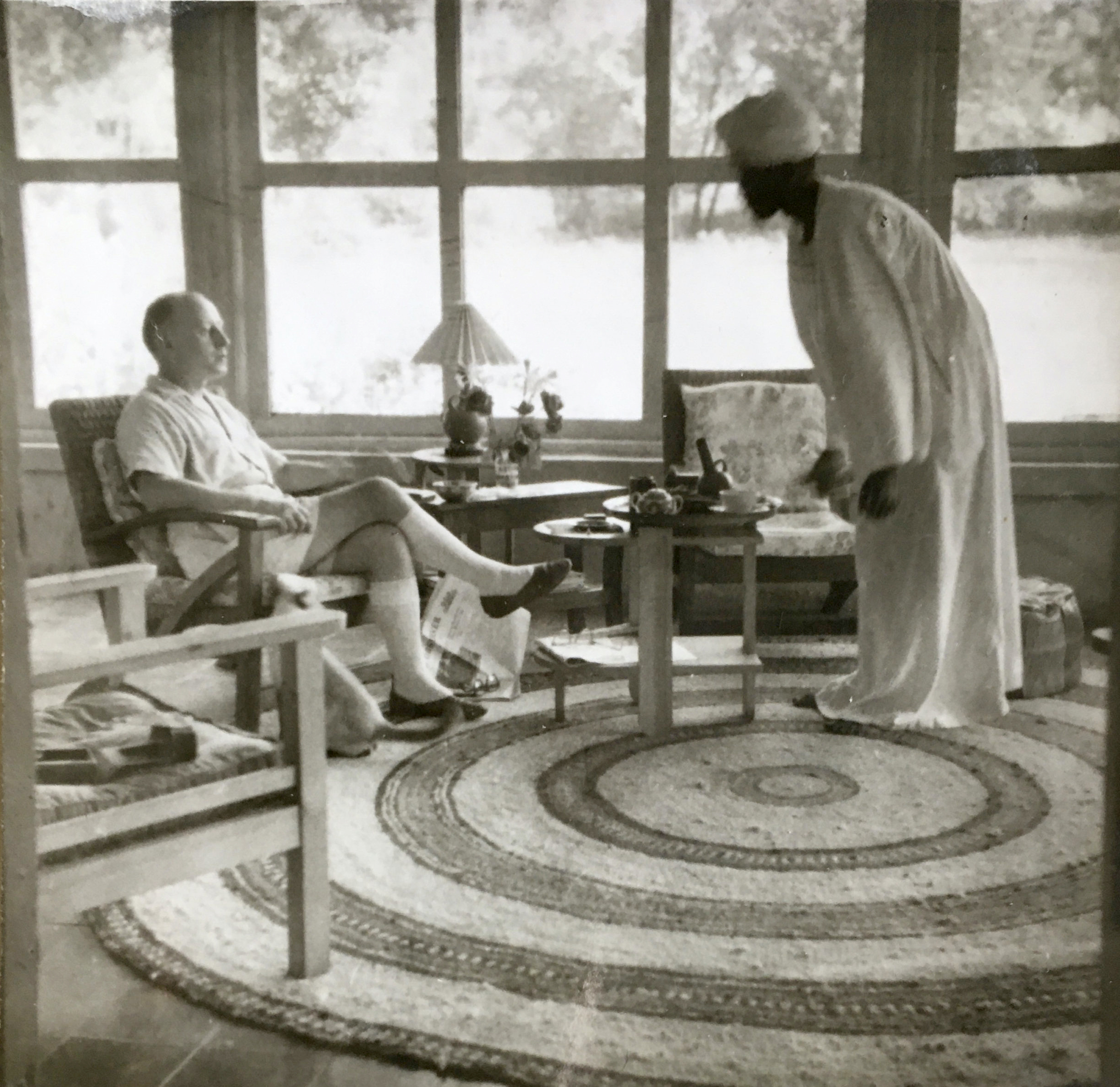

![]() My uncle Tadeusz Wąsowicz, PhD in Edaphology after the Warsaw University of Agricultural Sciences (SGGW), left Poland in November 1939 after the capitulation to avoid being interned by the occupant. He is 36 years old at that time and since leaving his family home in Warsaw he has been keeping a meticulous diary. Thanks to the help of friendly highlanders he made his way through the Tatra Mountains to the south and after a long journey – through Slovakia, Hungary and Yugoslavia – he joined the Polish army in France. The end of the war found him together with the Polish army in Scotland. After the war Tadeusz remained, like many Poles in distress, in England where he worked as a scientist and later taught at the London Borough Politechnic and the Imperial College of Agriculture in London where he died in 1967 at the age of 63.

My uncle Tadeusz Wąsowicz, PhD in Edaphology after the Warsaw University of Agricultural Sciences (SGGW), left Poland in November 1939 after the capitulation to avoid being interned by the occupant. He is 36 years old at that time and since leaving his family home in Warsaw he has been keeping a meticulous diary. Thanks to the help of friendly highlanders he made his way through the Tatra Mountains to the south and after a long journey – through Slovakia, Hungary and Yugoslavia – he joined the Polish army in France. The end of the war found him together with the Polish army in Scotland. After the war Tadeusz remained, like many Poles in distress, in England where he worked as a scientist and later taught at the London Borough Politechnic and the Imperial College of Agriculture in London where he died in 1967 at the age of 63.

![]() Mon oncle Tadeusz Wąsowicz, docteur en édaphologie à l’Ecole Supérieure d’Agricultures (SGGW), a quitté la Pologne en novembre 1939 après la capitulation pour éviter d’être interné par l’occupant. Il a alors 36 ans et, depuis qu’il a quitté la maison familiale à Varsovie, il tient un journal intime méticuleux. Grâce à l’aide des amis montagnards, il s’est frayé un chemin à travers les Tatras au sud et après un long voyage – à travers la Slovakie, la Hongrie et la Yougoslavie – il a rejoint l’armée polonaise en France. À la fin de la guerre, il se retrouve avec l’armée polonaise en Écosse. Après la guerre, Tadeusz, comme beaucoup de Polonais, moralement dechire, est resté en Angleterre où il a travaillé comme scientifique dans les tropiques et puis comme professeur à London Borough Politechnic et à l’Imperial College of Agriculture à Londres où il est décédé en 1967 à l’âge de 63 ans.

Mon oncle Tadeusz Wąsowicz, docteur en édaphologie à l’Ecole Supérieure d’Agricultures (SGGW), a quitté la Pologne en novembre 1939 après la capitulation pour éviter d’être interné par l’occupant. Il a alors 36 ans et, depuis qu’il a quitté la maison familiale à Varsovie, il tient un journal intime méticuleux. Grâce à l’aide des amis montagnards, il s’est frayé un chemin à travers les Tatras au sud et après un long voyage – à travers la Slovakie, la Hongrie et la Yougoslavie – il a rejoint l’armée polonaise en France. À la fin de la guerre, il se retrouve avec l’armée polonaise en Écosse. Après la guerre, Tadeusz, comme beaucoup de Polonais, moralement dechire, est resté en Angleterre où il a travaillé comme scientifique dans les tropiques et puis comme professeur à London Borough Politechnic et à l’Imperial College of Agriculture à Londres où il est décédé en 1967 à l’âge de 63 ans.

![]() Mijn oom Tadeusz Wąsowicz, doctor in de Edaphologie afgestudeerd aan de Warschause Universiteit voor Landbouwwetenschappen (SGGW), verliet Polen in november 1939 na de capitulatie om te voorkomen dat hij door de bezetter werd geïnterneerd. Hij is dan 36 jaar oud en vanaf de dag hij zijn familiehuis in Warschau heeft verlaten, houdt hij een nauwgezet dagboek bij. Dankzij de hulp van bevriende hooglanders baant hij zich een weg door het Tatragebergte naar het zuiden en na een lange reis – door Slowakije, Hongarije en Yugoslavia – sluit hij zich aan bij het Poolse Leger in Frankrijk. Het einde van de oorlog vond hem samen met het Poolse leger in Schotland. Na de oorlog bleef Tadeusz, zoals vele Polen vervuld van innerlijke strijd, in Engeland waar hij als wetenschapper werkte en waar hij in 1967 op 63-jarige leeftijd overleed.

Mijn oom Tadeusz Wąsowicz, doctor in de Edaphologie afgestudeerd aan de Warschause Universiteit voor Landbouwwetenschappen (SGGW), verliet Polen in november 1939 na de capitulatie om te voorkomen dat hij door de bezetter werd geïnterneerd. Hij is dan 36 jaar oud en vanaf de dag hij zijn familiehuis in Warschau heeft verlaten, houdt hij een nauwgezet dagboek bij. Dankzij de hulp van bevriende hooglanders baant hij zich een weg door het Tatragebergte naar het zuiden en na een lange reis – door Slowakije, Hongarije en Yugoslavia – sluit hij zich aan bij het Poolse Leger in Frankrijk. Het einde van de oorlog vond hem samen met het Poolse leger in Schotland. Na de oorlog bleef Tadeusz, zoals vele Polen vervuld van innerlijke strijd, in Engeland waar hij als wetenschapper werkte en waar hij in 1967 op 63-jarige leeftijd overleed.

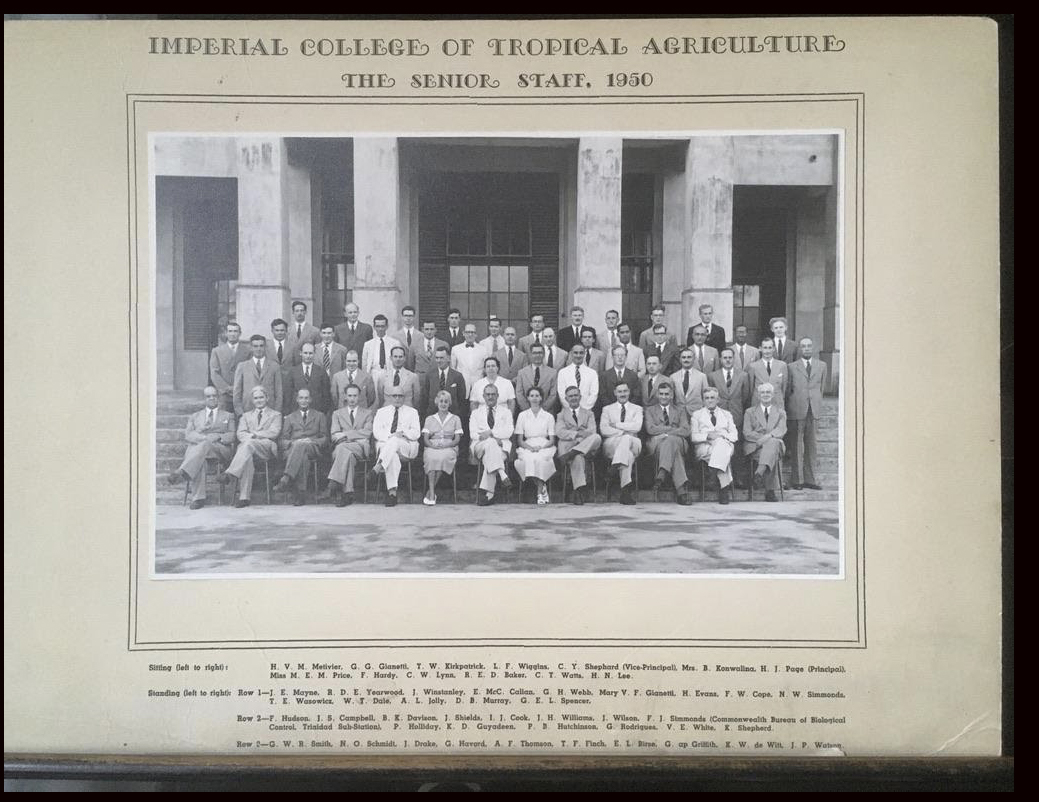

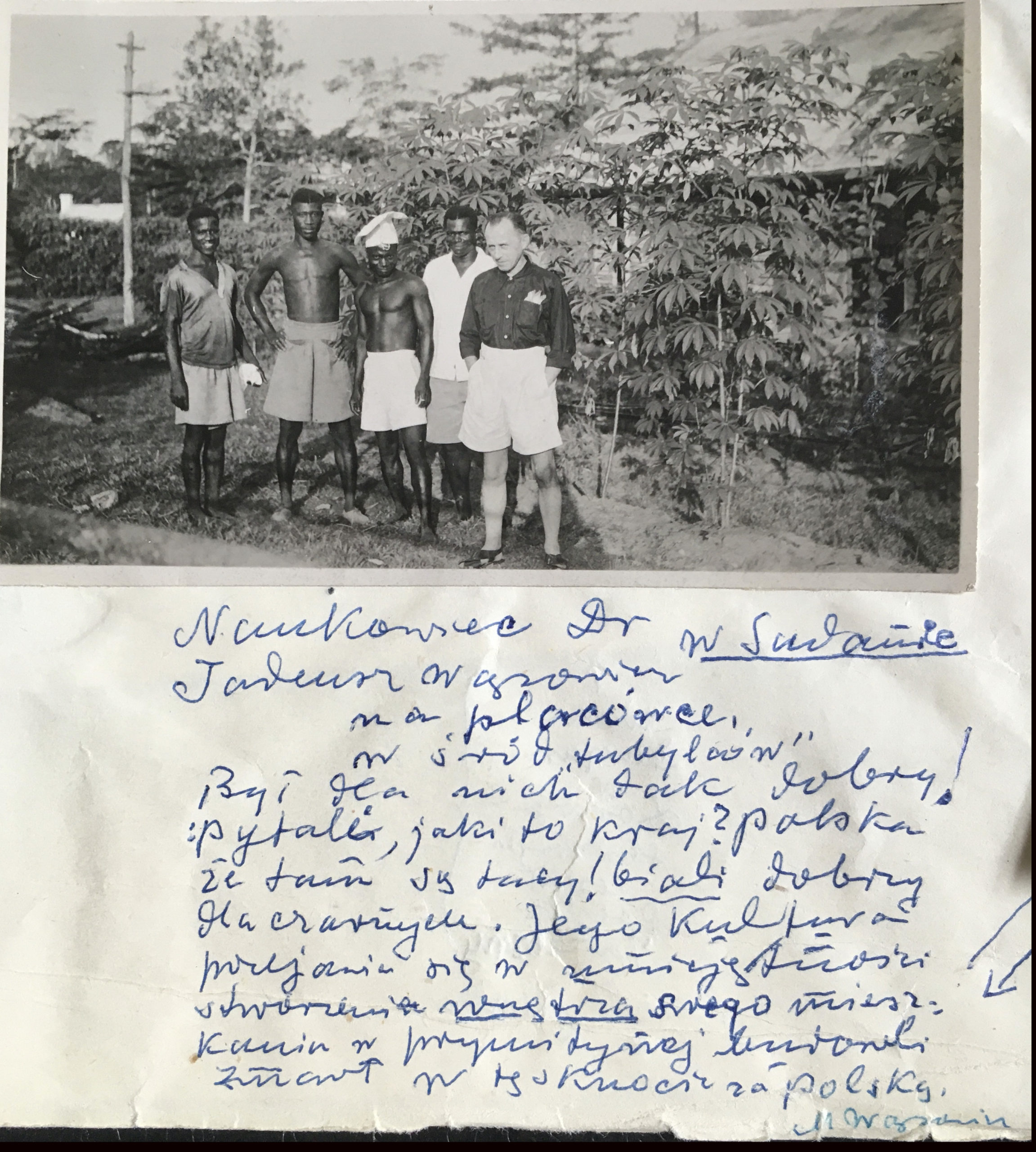

Tadeusz Wasowicz 1948 Gold Coast

Tadeusz Wasowicz – 2nd row 5th from the right.

[pl] Tadeusz Wąsowicz pracował też w tropikach jako gleboznawca. Miedzy innymi w Nigerii, Sudanie, Brytyjskiej Gujanie.

Znał i mówił kilkoma narzeczami arabskimi. Podobno był tak miły dla ludzi z którymi miał do czynienia,

że mówiąc o nim pytano – ‘jaki to jest kraj ta Polska, że tam są tacy biali dobrzy dla czarnych’?

[eng] Tadeusz Wąsowicz also worked in the tropics, among others in Nigeria, Sudan, British Guyana, as a soil expert. He knew and spoke several Arabic languages. Apparently, he was so kind to the people he was dealing with that they said, while talking about him,”what kind of a country is this Poland that there are white people good for the blacks?”

[fr] Tadeusz Wąsowicz a également travaillé dans les tropiques en tant qu’expert des sols. Entre autres au Nigeria, au Soudan, en Guyane britannique. Il connaissait et parlait plusieurs langues arabes. Apparemment, il était si sympatique envers son equippe

qu’ils lui posaient des questions sur lui -“Quel genre de pays est cette Pologne d’où viennent des blancs si bons pour les noirs?

[nl] Tadeusz Wąsowicz werkte ook in de tropen als bodemdeskundige. Onder andere in Nigeria, Soedan, Brits Guyana.

Hij kende en sprak verschillende Arabische talen. Blijkbaar was hij zo vriendelijk voor de mensen waar hij mee werkte dat sprekend over hem vroegen zij … “Wat voor een land is dit Polen dat daar witte mensen zijn die goed zijn voor zwarten ?”

![]() Po śmierci Stalina stopniowo zaczęły ożywać kontakty z Europą zachodnią. Jak wielu Polaków pozostałych po wojnie poza krajem stryj Tadeusz po nieustannych staraniach odnalazł kontakt z młodszym bratem Dariuszem i dowiedział się o tragicznych losach rodziny w Warszawie. Bracia uściskali się znowu dopiero po 25 latach w 1965 roku, kiedy Ojczulek dostał zezwolenie na wyjazd do Anglii w celu odwiedzenia chorego brata, w polskim szpitalu Mabledon niedaleko Londynu.

Po śmierci Stalina stopniowo zaczęły ożywać kontakty z Europą zachodnią. Jak wielu Polaków pozostałych po wojnie poza krajem stryj Tadeusz po nieustannych staraniach odnalazł kontakt z młodszym bratem Dariuszem i dowiedział się o tragicznych losach rodziny w Warszawie. Bracia uściskali się znowu dopiero po 25 latach w 1965 roku, kiedy Ojczulek dostał zezwolenie na wyjazd do Anglii w celu odwiedzenia chorego brata, w polskim szpitalu Mabledon niedaleko Londynu.

![]() After Stalin’s death, the contacts with Western Europe gradually began to come alive. Like many Poles who remained outside the country after the war, Uncle Tadeusz, after constant efforts, regained contact with his younger brother Dariusz and learned about the tragic fate of the family in Warsaw. The brothers hugged each other again only after 25 years in 1965, when Ojczulek was allowed, by the authorities, to leave Poland to visit his sick brother Tadeusz in the Polish hospital Mabledon near London.

After Stalin’s death, the contacts with Western Europe gradually began to come alive. Like many Poles who remained outside the country after the war, Uncle Tadeusz, after constant efforts, regained contact with his younger brother Dariusz and learned about the tragic fate of the family in Warsaw. The brothers hugged each other again only after 25 years in 1965, when Ojczulek was allowed, by the authorities, to leave Poland to visit his sick brother Tadeusz in the Polish hospital Mabledon near London.

![]() Après la mort de Staline, les contacts avec l’Europe occidentale se sont peu à peu concrétisés. Comme beaucoup de Polonais restés hors du pays après la guerre, l’oncle Tadeusz, après des efforts constants, a repris contact avec son jeune frère Dariusz et a appris le destin tragique de la famille à Varsovie. Les frères ne se sont à nouveau embrassés qu’après 25 ans, en 1965, lorsque Ojczulek a été autorisé à aller en Angleterre pour rendre visite à son frère Tadeusz malade à l’hôpital polonais de Mabledon, près de Londres.

Après la mort de Staline, les contacts avec l’Europe occidentale se sont peu à peu concrétisés. Comme beaucoup de Polonais restés hors du pays après la guerre, l’oncle Tadeusz, après des efforts constants, a repris contact avec son jeune frère Dariusz et a appris le destin tragique de la famille à Varsovie. Les frères ne se sont à nouveau embrassés qu’après 25 ans, en 1965, lorsque Ojczulek a été autorisé à aller en Angleterre pour rendre visite à son frère Tadeusz malade à l’hôpital polonais de Mabledon, près de Londres.

![]() Na de dood van Stalin kwamen de contacten met West-Europa geleidelijk aan tot leven. Zoals vele Polen die na de oorlog buiten het land zijn gebleven, hervond oom Tadeusz na voortdurende inspanningen contact met zijn jongere broer Dariusz en leerde hij over het tragische lot van de familie in Warschau. De broers omhelsden elkaar pas weer na 25 jaar in 1965, toen ‘Ojczulek” toestemming kreeg naar Engeland te gaan om zijn zieke broer Tadeusz te bezoeken in het Poolse ziekenhuis Mabledon bij Londen.

Na de dood van Stalin kwamen de contacten met West-Europa geleidelijk aan tot leven. Zoals vele Polen die na de oorlog buiten het land zijn gebleven, hervond oom Tadeusz na voortdurende inspanningen contact met zijn jongere broer Dariusz en leerde hij over het tragische lot van de familie in Warschau. De broers omhelsden elkaar pas weer na 25 jaar in 1965, toen ‘Ojczulek” toestemming kreeg naar Engeland te gaan om zijn zieke broer Tadeusz te bezoeken in het Poolse ziekenhuis Mabledon bij Londen.

Bracia Tadeusz i Dariusz w ogrodzie szpitala Mabledon w lipcu 1965.

Brothers Tadeusz and Dariusz in the garden of Mabledon Hospital in July 1965

Les frères Tadeusz et Dariusz dans le jardin de l’hôpital de Mabledon en juillet 1965

De broers Tadeusz en Dariusz in de tuin van het Mabledon-ziekenhuis, juli 1965.

![]() Stryjek Tadeusz postanowił dać swoim nowym bratanicom i bratankowi w Polsce prezent w formie języka angielskiego i wymyślił plan, który nazwał “A window open to the world”. Przez całe lata wydreptywał progi zarówno polskiej ambasady jak i Home Office w Londynie, aż w końcu – nie do wiary – uzyskał pozwolenie na przyjazd najstarszej bratanicy 12 letniej Darii na pełny rok szkolny do Anglii. Po jej powrocie pojechałam na rok ja, Gabryela, i po mnie najmłodsza z nas Blanka. Jacek wykorzystał prezent Stryjka, studiując skrzypce w Brukseli dopiero po śmierci Stryjka, który po swojemu też i o to skrupulatnie zadbał.

Stryjek Tadeusz postanowił dać swoim nowym bratanicom i bratankowi w Polsce prezent w formie języka angielskiego i wymyślił plan, który nazwał “A window open to the world”. Przez całe lata wydreptywał progi zarówno polskiej ambasady jak i Home Office w Londynie, aż w końcu – nie do wiary – uzyskał pozwolenie na przyjazd najstarszej bratanicy 12 letniej Darii na pełny rok szkolny do Anglii. Po jej powrocie pojechałam na rok ja, Gabryela, i po mnie najmłodsza z nas Blanka. Jacek wykorzystał prezent Stryjka, studiując skrzypce w Brukseli dopiero po śmierci Stryjka, który po swojemu też i o to skrupulatnie zadbał.

![]() Uncle Tadeusz decided to give his new nephew and nieces in Poland a gift in the form of English language and came up with a plan he called “A window open to the world”. For years, he was treading the thresholds of both the Polish embassy and the Home Office in London, until finally, unbelievably enough, he obtained the permission for Daria, his eldest niece of 12 years old, to come to England for a full school year. After her return, I, Gabryela, went to England, followed subsequently by the youngest of us, Blanka. Jacek used his uncle’s gift to study the violin in Brussels only after the death of uncle Tadeusz who, in his will, took care meticulously also of that.

Uncle Tadeusz decided to give his new nephew and nieces in Poland a gift in the form of English language and came up with a plan he called “A window open to the world”. For years, he was treading the thresholds of both the Polish embassy and the Home Office in London, until finally, unbelievably enough, he obtained the permission for Daria, his eldest niece of 12 years old, to come to England for a full school year. After her return, I, Gabryela, went to England, followed subsequently by the youngest of us, Blanka. Jacek used his uncle’s gift to study the violin in Brussels only after the death of uncle Tadeusz who, in his will, took care meticulously also of that.

![]() L’oncle Tadeusz a décidé de faire un cadeau à ses nouveaux neveu et nièces en Pologne sous la forme de la langue anglaise et il a élaboré un plan qu’il a appelé “Une fenêtre ouverte sur le monde”. Pendant des années, il a insiste sans cesse auprès l’ambassade de Pologne et du ministère de l’Intérieur à Londres, jusqu’à ce qu’il obtienne finalement – chose incroyable – la permission pour la nièce aînée Daria, 12 ans, de venir en Angleterre pour un séjour d’une année scolaire complète. Après son retour, c’est moi, Gabryela, qui suis partie en Angleterre, et puis la plus jeune d’entre nous, Blanka. Jacek a utilisé le don de son oncle pour étudier le violon à Bruxelles seulement après la mort de oncle Tadeusz, qui s’en est également occupé avec soin.

L’oncle Tadeusz a décidé de faire un cadeau à ses nouveaux neveu et nièces en Pologne sous la forme de la langue anglaise et il a élaboré un plan qu’il a appelé “Une fenêtre ouverte sur le monde”. Pendant des années, il a insiste sans cesse auprès l’ambassade de Pologne et du ministère de l’Intérieur à Londres, jusqu’à ce qu’il obtienne finalement – chose incroyable – la permission pour la nièce aînée Daria, 12 ans, de venir en Angleterre pour un séjour d’une année scolaire complète. Après son retour, c’est moi, Gabryela, qui suis partie en Angleterre, et puis la plus jeune d’entre nous, Blanka. Jacek a utilisé le don de son oncle pour étudier le violon à Bruxelles seulement après la mort de oncle Tadeusz, qui s’en est également occupé avec soin.

![]() Oom Tadeusz besloot zijn nieuw neefje en nichtjes in Polen een cadeau in de vorm van Engelse taal te geven en kwam met een plan dat hij “Een venster naar de wereld” noemde. Jarenlang liep hij de drempels plat van zowel de Poolse ambassade als het ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken in Londen, totdat hij uiteindelijk, onvoorstelbaar genoeg, toestemming kreeg om Daria, het oudste nichtje van 12 jaar, voor een volledig schooljaar naar Engeland te laten komen. Na haar terugkeer ging ik, Gabryela, naar Engeland en vervolgens, de jongste van ons, Blanka. Jacek gebruikte de gift van zijn oom, om in Brussel viool te studeren, pas na de dood van oom Tadeusz die ook daarvoor zorgvuldig en vooruitziend heeft gezorgd.

Oom Tadeusz besloot zijn nieuw neefje en nichtjes in Polen een cadeau in de vorm van Engelse taal te geven en kwam met een plan dat hij “Een venster naar de wereld” noemde. Jarenlang liep hij de drempels plat van zowel de Poolse ambassade als het ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken in Londen, totdat hij uiteindelijk, onvoorstelbaar genoeg, toestemming kreeg om Daria, het oudste nichtje van 12 jaar, voor een volledig schooljaar naar Engeland te laten komen. Na haar terugkeer ging ik, Gabryela, naar Engeland en vervolgens, de jongste van ons, Blanka. Jacek gebruikte de gift van zijn oom, om in Brussel viool te studeren, pas na de dood van oom Tadeusz die ook daarvoor zorgvuldig en vooruitziend heeft gezorgd.

Tadeusz with Daria – London 1958

Southhampton M/S Batory – sending Daria back to Poland 29-7-1959

Trafagar Square 11-9-1960 – Gabryela

TrafalgarSquare 27-7-1961 – Gabryela

M/S Jaroslaw Dabrowski – Thames, London – sending Gabryela back home to Poland.

![]() Życie mojego Ojczulka jest przykładem losów wielu Warszawiaków i ich rodzin. Urodził się 1 grudnia 1909 roku jako najmłodszy syn artysty malarza Rafała Wąsowicza i pianistki Anieli Wespańskiej. W paszporcie miał jednak datę urodzenia 10 stycznia 1910 roku, bo zameldowano go w urzędzie stanu cywilnego po Nowym Roku dla odroczenia o rok obowiązku służby wojskowej. Mały Dariusz był rozrabiaką, więc został posłany przez ojca Rafała do Korpusu Kadetów w Modlinie. Podobno domownicy w Warszawie wiedzieli kiedy za karę nie miał pozwolenia na wyjazd do domu na niedzielę, bo jego pies Fidel leżał sobie spokojnie w kuchni, a nie czekał jak zwykle na Darka przy drzwiach wejściowych. Ojczulek niewiele mówił o swoim życiu przedwojennym i w latach okupacji, a jeśli pytaliśmy to opowiadał raczej właśnie takie zabawne historie ze swojego dzieciństwa i młodości.

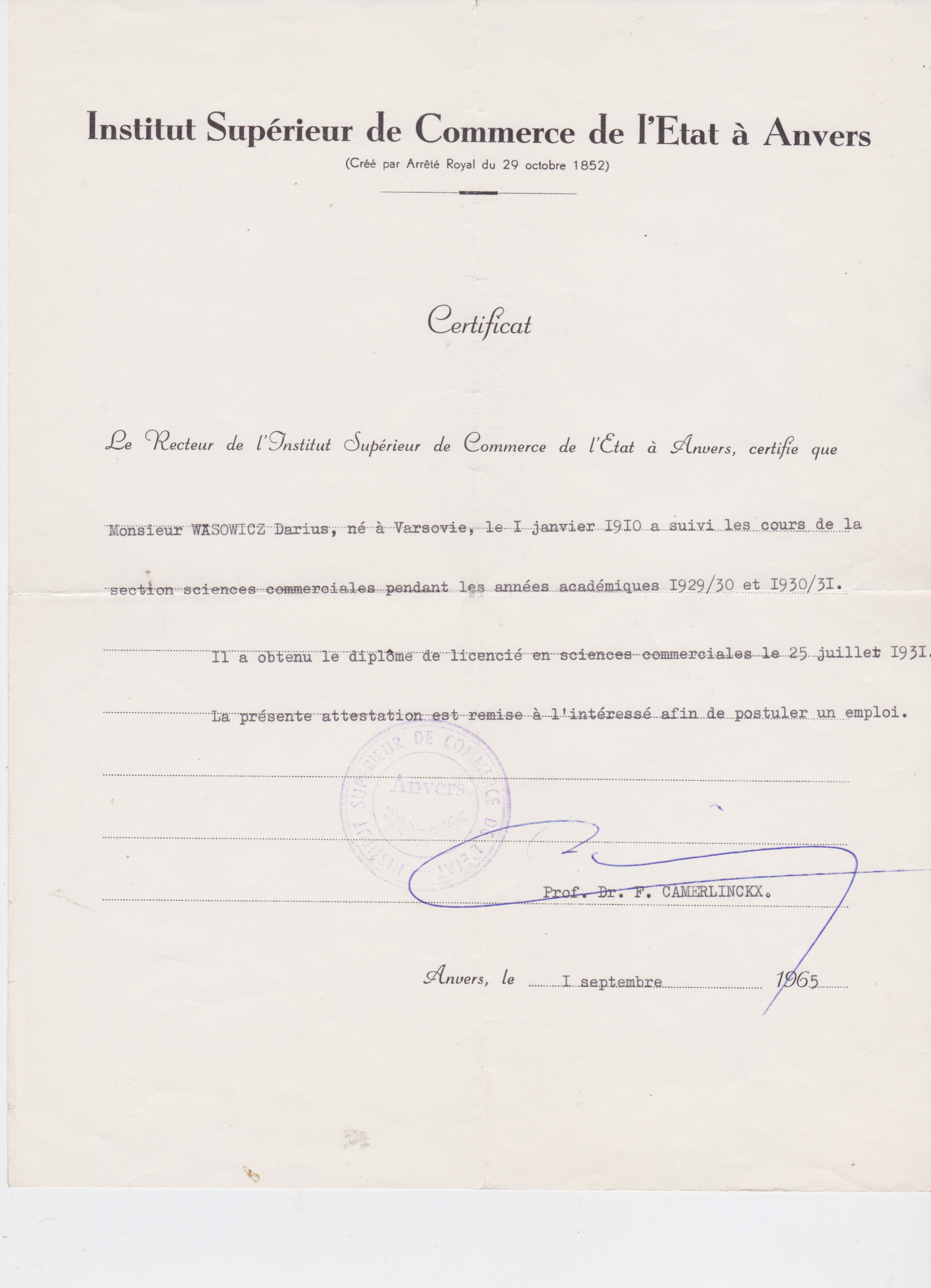

Dariusz marzył o studiach malarskich lub przynajmniej o architekturze. Jednak ojciec Rafał miał inne plany dla najmłodszego syna, jako że w rodzinie była już jedna artystka – jego najstarsza córka Maria i wysłał Darka do Belgii na studia handlu zagranicznego na Institut Supérieure de Commerce de L’Etat w Antwerpii, gdzie w tamtych czasach studiowało sporo Polaków.

Życie mojego Ojczulka jest przykładem losów wielu Warszawiaków i ich rodzin. Urodził się 1 grudnia 1909 roku jako najmłodszy syn artysty malarza Rafała Wąsowicza i pianistki Anieli Wespańskiej. W paszporcie miał jednak datę urodzenia 10 stycznia 1910 roku, bo zameldowano go w urzędzie stanu cywilnego po Nowym Roku dla odroczenia o rok obowiązku służby wojskowej. Mały Dariusz był rozrabiaką, więc został posłany przez ojca Rafała do Korpusu Kadetów w Modlinie. Podobno domownicy w Warszawie wiedzieli kiedy za karę nie miał pozwolenia na wyjazd do domu na niedzielę, bo jego pies Fidel leżał sobie spokojnie w kuchni, a nie czekał jak zwykle na Darka przy drzwiach wejściowych. Ojczulek niewiele mówił o swoim życiu przedwojennym i w latach okupacji, a jeśli pytaliśmy to opowiadał raczej właśnie takie zabawne historie ze swojego dzieciństwa i młodości.

Dariusz marzył o studiach malarskich lub przynajmniej o architekturze. Jednak ojciec Rafał miał inne plany dla najmłodszego syna, jako że w rodzinie była już jedna artystka – jego najstarsza córka Maria i wysłał Darka do Belgii na studia handlu zagranicznego na Institut Supérieure de Commerce de L’Etat w Antwerpii, gdzie w tamtych czasach studiowało sporo Polaków.

![]() The life of my Ojczulek is an example of the fate of many Warsaw citizens and their families. He was born on December 1st, 1909 as the youngest son of the artist-painter Rafał Wąsowicz and the pianist Aniela Wespańska. In his passport, however, he had his date of birth on January 10 ,1910 because, in order to postpone his military service for a year, he was registered after New Year’s Day. Little Dariusz was a lively troublemaker, so he was sent by his father Rafał to the Cadet Corps School in Modlin. Apparently, the Warsaw home residents knew when, as a punishment, he was not allowed to go home for the Sunday, because his dog Fidel was not waiting for Darek at the front door as usual, but was lying quietly in the kitchen. Ojczulek didn’t talk much about his pre-war life and the years of the German occupation, and if we asked, he told rather such funny stories from his childhood and youth.

Dariusz dreamt of studying painting or at least architecture. However, father Rafał had other plans for his youngest son, as there was already one artist in the family – his eldest daughter Maria – and he sent Dariusz to Belgium to study foreign trade at the Institut Supérieure de Commerce de L’Etat in Antwerp, where more Poles studied at the time.

The life of my Ojczulek is an example of the fate of many Warsaw citizens and their families. He was born on December 1st, 1909 as the youngest son of the artist-painter Rafał Wąsowicz and the pianist Aniela Wespańska. In his passport, however, he had his date of birth on January 10 ,1910 because, in order to postpone his military service for a year, he was registered after New Year’s Day. Little Dariusz was a lively troublemaker, so he was sent by his father Rafał to the Cadet Corps School in Modlin. Apparently, the Warsaw home residents knew when, as a punishment, he was not allowed to go home for the Sunday, because his dog Fidel was not waiting for Darek at the front door as usual, but was lying quietly in the kitchen. Ojczulek didn’t talk much about his pre-war life and the years of the German occupation, and if we asked, he told rather such funny stories from his childhood and youth.

Dariusz dreamt of studying painting or at least architecture. However, father Rafał had other plans for his youngest son, as there was already one artist in the family – his eldest daughter Maria – and he sent Dariusz to Belgium to study foreign trade at the Institut Supérieure de Commerce de L’Etat in Antwerp, where more Poles studied at the time.

![]() La vie de mon père est un exemple du destin de nombreux citoyens de Varsovie et de leurs familles. Il est né le 1er décembre 1909 comme le plus jeune fils de l’artiste-peintre Rafał Wąsowicz et de la pianiste Aniela Wespańska. Dans son passeport, cependant, sa date de naissance était le 10 janvier 1910, car il a été inscrit au bureau de l’état civil après la veille du Nouvel An pour reporter son service militaire d’un an. Le petit Dariusz était un fauteur de troubles, il a donc été envoyé par son père Rafał à l’école du corps de cadets de Modlin. Apparemment, les habitants de Varsovie savaient quand, en guise de punition, il n’était pas autorisé à rentrer chez lui le dimanche, car son chien Fidel était couché tranquillement dans la cuisine et n’attendait pas Darek à la porte d’entrée comme d’habitude. Ojczulek ne parlait pas beaucoup de sa vie d’avant-guerre et des années d’occupation, et si on lui demandait, il racontait plutôt des histoires drôles de son enfance et de sa jeunesse. Dariusz rêvait d’étudier la peinture ou au moins l’architecture. Cependant, le père Rafał avait d’autres projets pour son fils cadet, car il y avait déjà un artiste dans la famille – sa fille aînée Maria – et il a envoyé Dariusz étudier le commerce extérieur à l’Institut supérieur de commerce de l’État à Anvers, où à l’époque, de nombreux Polonais étudiaient.

La vie de mon père est un exemple du destin de nombreux citoyens de Varsovie et de leurs familles. Il est né le 1er décembre 1909 comme le plus jeune fils de l’artiste-peintre Rafał Wąsowicz et de la pianiste Aniela Wespańska. Dans son passeport, cependant, sa date de naissance était le 10 janvier 1910, car il a été inscrit au bureau de l’état civil après la veille du Nouvel An pour reporter son service militaire d’un an. Le petit Dariusz était un fauteur de troubles, il a donc été envoyé par son père Rafał à l’école du corps de cadets de Modlin. Apparemment, les habitants de Varsovie savaient quand, en guise de punition, il n’était pas autorisé à rentrer chez lui le dimanche, car son chien Fidel était couché tranquillement dans la cuisine et n’attendait pas Darek à la porte d’entrée comme d’habitude. Ojczulek ne parlait pas beaucoup de sa vie d’avant-guerre et des années d’occupation, et si on lui demandait, il racontait plutôt des histoires drôles de son enfance et de sa jeunesse. Dariusz rêvait d’étudier la peinture ou au moins l’architecture. Cependant, le père Rafał avait d’autres projets pour son fils cadet, car il y avait déjà un artiste dans la famille – sa fille aînée Maria – et il a envoyé Dariusz étudier le commerce extérieur à l’Institut supérieur de commerce de l’État à Anvers, où à l’époque, de nombreux Polonais étudiaient.

![]() Het leven van mijn vader ‘Ojczulek’ is een voorbeeld van het lot van veel Warschau bewoners en hun families. Hij werd op 1 december 1909 geboren als jongste zoon van de kunstschilder Rafał Wąsowicz en de pianiste Aniela Wespańska. In zijn paspoort was echter zijn geboortedatum op 10 januari 1910, omdat hij pas na Nieuwjaarsdag in de griffie werd ingeschreven om zijn militaire dienst met een jaar uit te stellen. De kleine Dariusz was een uigelaten kind, dus werd hij door zijn vader Rafał naar het Cadetten Corps School in Modlin gestuurd. Blijkbaar wist de familie in Warschau wanneer hij voor straf op zondag niet naar huis mocht, omdat zijn hond Fidel niet, zoals gewoonlijk, bij de voordeur op Darek wachtte maar rustig in de keuken lag. Ojczulek sprak niet veel over zijn vooroorlogse leven en de jaren van de Duitse bezetting, en als wij het vroegen, vertelde hij vooral zulke grappige verhalen uit zijn kindertijd en jeugd. Dariusz droomde van eenkunst studie of in ieder geval architectuur. Vader Rafał had echter andere plannen voor zijn jongste zoon, want er was al een kunstenaar in de familie – zijn oudste dochter Maria – en hij stuurde Darek naar Belgie om buitenlandse handel te studeren aan het Institut Supérieure de Commerce de L’Etat in Antwerpen, waar meer Polen in die tijd studeerden.

Het leven van mijn vader ‘Ojczulek’ is een voorbeeld van het lot van veel Warschau bewoners en hun families. Hij werd op 1 december 1909 geboren als jongste zoon van de kunstschilder Rafał Wąsowicz en de pianiste Aniela Wespańska. In zijn paspoort was echter zijn geboortedatum op 10 januari 1910, omdat hij pas na Nieuwjaarsdag in de griffie werd ingeschreven om zijn militaire dienst met een jaar uit te stellen. De kleine Dariusz was een uigelaten kind, dus werd hij door zijn vader Rafał naar het Cadetten Corps School in Modlin gestuurd. Blijkbaar wist de familie in Warschau wanneer hij voor straf op zondag niet naar huis mocht, omdat zijn hond Fidel niet, zoals gewoonlijk, bij de voordeur op Darek wachtte maar rustig in de keuken lag. Ojczulek sprak niet veel over zijn vooroorlogse leven en de jaren van de Duitse bezetting, en als wij het vroegen, vertelde hij vooral zulke grappige verhalen uit zijn kindertijd en jeugd. Dariusz droomde van eenkunst studie of in ieder geval architectuur. Vader Rafał had echter andere plannen voor zijn jongste zoon, want er was al een kunstenaar in de familie – zijn oudste dochter Maria – en hij stuurde Darek naar Belgie om buitenlandse handel te studeren aan het Institut Supérieure de Commerce de L’Etat in Antwerpen, waar meer Polen in die tijd studeerden.

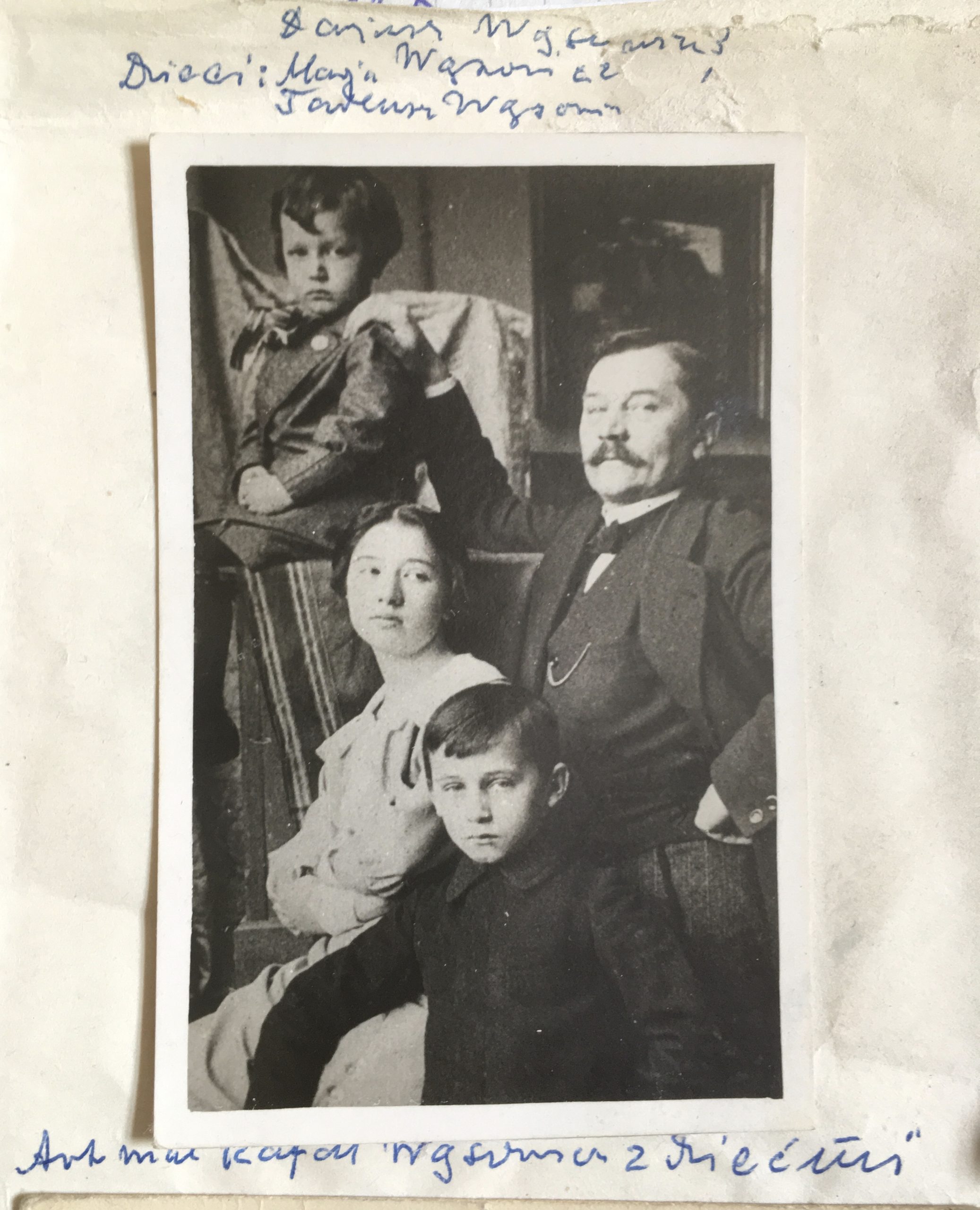

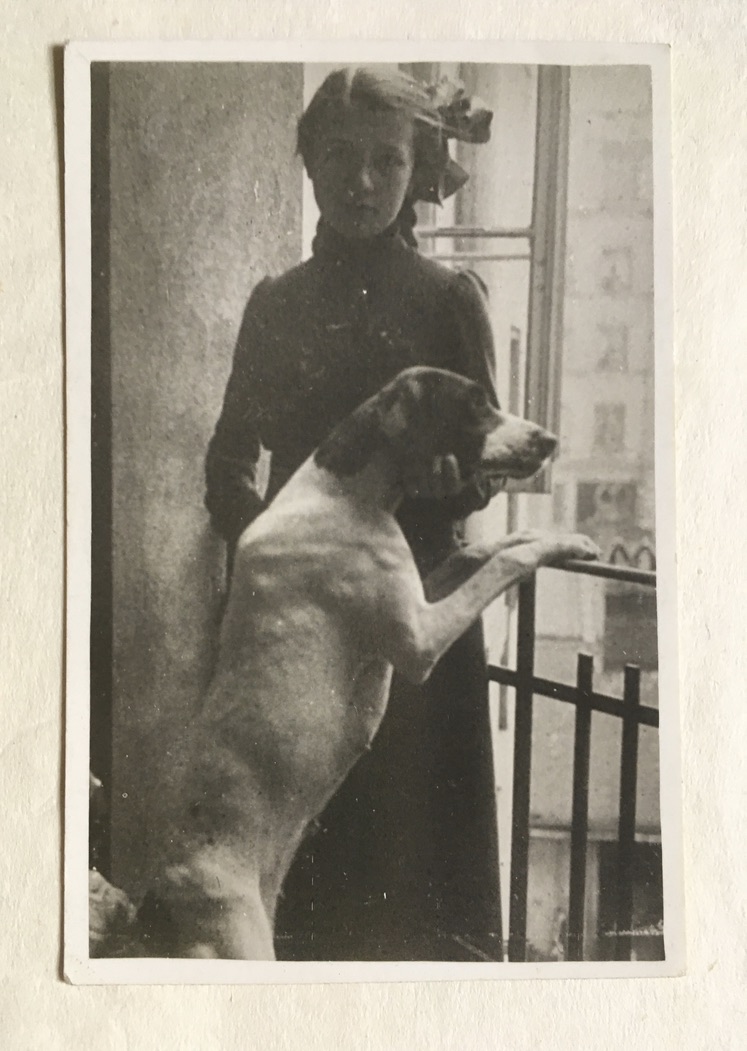

Dom Rafała Wąsowicza, ul Wolska 7 (foto – 1918). Tu urodził się mój Ojczulek Dariusz. Na najwyższym piętrze widoczne duże okna pracowni malarskiej gdzie w czasie okupacji pod okiem ojca Dariusz doskonalił swój warsztat malarski. ( foto 1913 ) Rafal z dziecmi – (foto ca. 1915) Maryla i pies Fidel (?)

Rafał Wąsowicz’s house, 7 Wolska Street. (photo – 1918). My father Dariusz was born here. On the top floor you can see the large windows of the painting studio where, during the occupation Dariusz was perfecting his painting skills under the supervision of his father. (photo 1913) Rafal with his children (photo ca. 1915) Maryla with dog Fidel (?)

La maison de Rafał Wąsowicz, 7 rue Wolska, Varsovie, (photo – 1918). Mon père Dariusz est né ici.

Au dernier étage, sont visibles les grandes fenêtres de l’atelier de peinture où, pendant l’occupation sous la supervision de mon grand-père Rafal, Dariusz perfectionnait son métier de peintre.- (photo 1913) Rafal avec ces enfants – (photo ca 1915) Maryla avec chien Fidel (?)

Het huis van Rafał Wąsowicz, 7 Wolska Street,(foto – 1918). Mijn vader Dariusz is hier geboren. Op de bovenste verdieping zie je de grote ramen van het schildersatelier waar Dariusz tijdens de bezetting onder toezicht van zijn vader zijn schilders-metier aan het perfectioneren was. – (foto 1913) Rafal met zijn kinderen – (foto ca. 1915) Maryla met hond Fidel (?)

Rafal Wasowicz Narcyza Wasowicz – Hanna Wasowicz

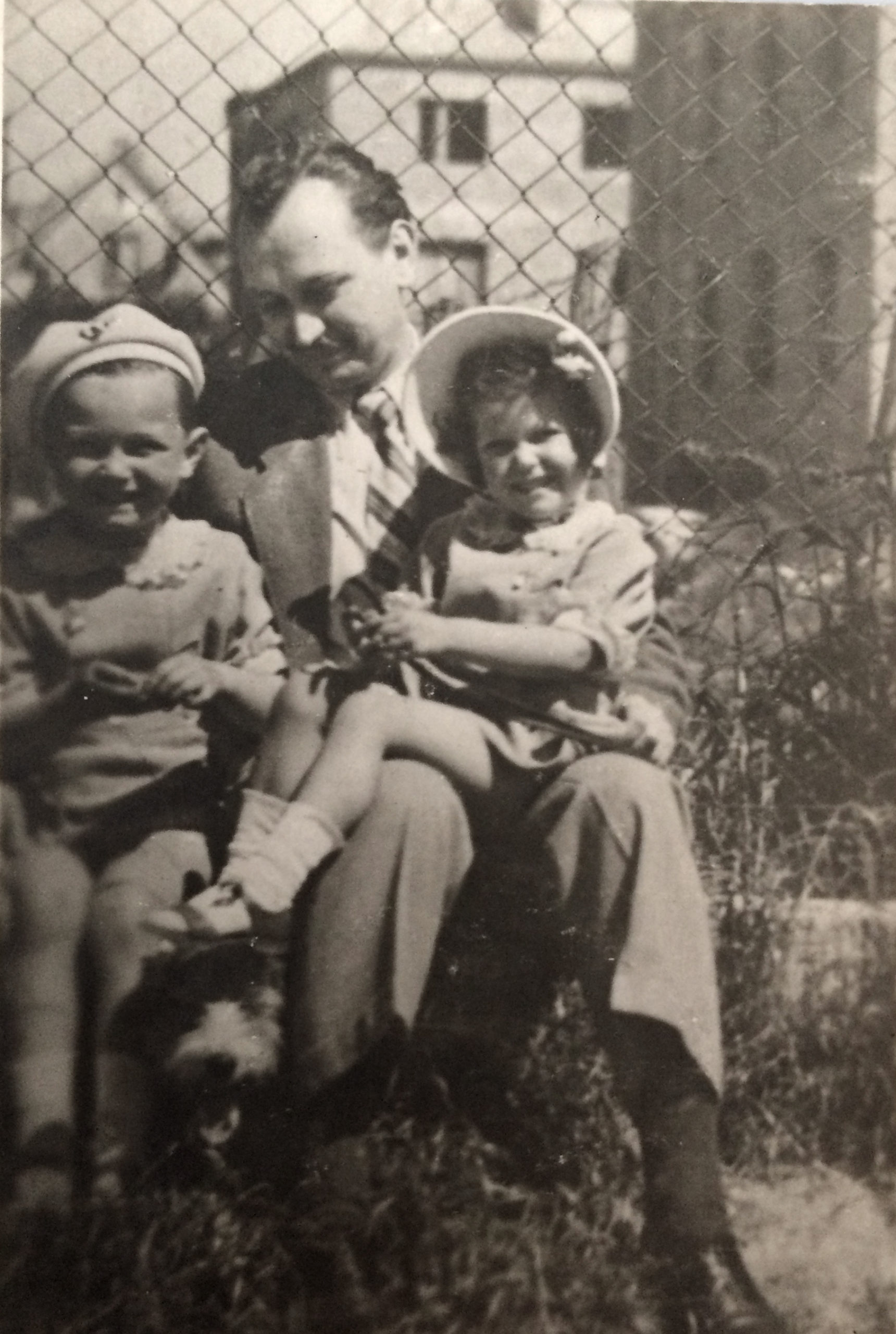

[pl] Dariusz Wąsowicz z dziećmi Rafałem Narcyzą i z ich psem. Zdjęcia zrobione w latach okupacji przed sierpniem 1944 roku schował Dariusz do kieszonki marynarki, kiedy opuszczając rodzinny dom żegnał Ojca, żonę i dzieci.

[eng] Dariusz with his children Rafał Narcyza and their dog, these photos were taken during the occupation years before August 1944. Dariusz put these pictures in his jacket pocket when he fled his family home saying goodbye to his father, wife and children.

[fr] Dariusz Wąsowicz avec les enfants Rafał, Narcyzka et leur chien. La photo a été prise pendant les années d’occupation, avant le 1er août 1944.Dariusz a glissé cette photo dans la poche de sa veste lorsqu’il a quitté la maison familiale.

[nl] Dariusz met kinderen Rafał Narcyza en hun hond, foto’s genomen tijdens de bezettingsjaren voor augustus 1944. Dariusz schoof deze foto’s in zijn borstszakje toen hij zijn familiehuis verliet en afscheid nam van zijn vader, vrouw en kinderen.

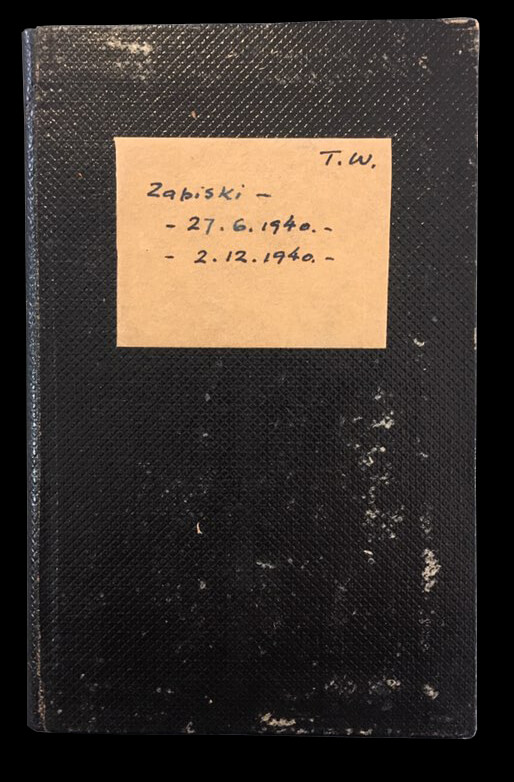

![]() Nie wiedział, że kilka dni później, 6 sierpnia 1944 rano w Rzezi Woli jego rodzina zginęła z rąk faszystowskich: 77 letni ojciec Rafał, żona Hanna wraz z 10 letnim synkiem Rafałem i 7 letnia córeczką Narcyzką oraz inni, daremnie chroniący się w piwnicy, mieszkańcy domu na ulicy Wolskiej. Powstanie upadło, ale odwet Niemców trwał i Warszawa płonęła. Spopielone resztki swych bliskich odnalazł Dariusz w piwnicy zgliszcz swego domu dopiero w styczniu 1945 roku po zajęciu ruin Warszawy przez wojska radzieckie. Do jeszcze hermetycznie zamkniętej stolicy wpuścił go wartujący radziecki żołnierz za kawałek chleba.

Nie wiedział, że kilka dni później, 6 sierpnia 1944 rano w Rzezi Woli jego rodzina zginęła z rąk faszystowskich: 77 letni ojciec Rafał, żona Hanna wraz z 10 letnim synkiem Rafałem i 7 letnia córeczką Narcyzką oraz inni, daremnie chroniący się w piwnicy, mieszkańcy domu na ulicy Wolskiej. Powstanie upadło, ale odwet Niemców trwał i Warszawa płonęła. Spopielone resztki swych bliskich odnalazł Dariusz w piwnicy zgliszcz swego domu dopiero w styczniu 1945 roku po zajęciu ruin Warszawy przez wojska radzieckie. Do jeszcze hermetycznie zamkniętej stolicy wpuścił go wartujący radziecki żołnierz za kawałek chleba.

![]() He did not know that a few days later, on the morning of August 6, 1944, during the Slaugter of Wola, his family died at the hands of fascists: 77-year-old father Rafał, wife Hanna together with her 10-year-old son Rafał and 7-year-old daughter Narcyza and other, vainly hiding in the basement, inhabitants of the house on Wolska Street. The uprising fell, but the Germans’ retaliation continued and Warsaw was burning. The burnt remains of his loved ones were found by Dariusz in the basement of his destroyed house only in January 1945, after the ruins of Warsaw were taken over by the Soviet army. He was let into the still hermetically sealed capital by a Soviet soldier standing on guard in exchange for a piece of bread.

He did not know that a few days later, on the morning of August 6, 1944, during the Slaugter of Wola, his family died at the hands of fascists: 77-year-old father Rafał, wife Hanna together with her 10-year-old son Rafał and 7-year-old daughter Narcyza and other, vainly hiding in the basement, inhabitants of the house on Wolska Street. The uprising fell, but the Germans’ retaliation continued and Warsaw was burning. The burnt remains of his loved ones were found by Dariusz in the basement of his destroyed house only in January 1945, after the ruins of Warsaw were taken over by the Soviet army. He was let into the still hermetically sealed capital by a Soviet soldier standing on guard in exchange for a piece of bread.

![]() Il ne savait pas que quelques jours plus tard, le 6 août 1944, dans le Massacre de Wola, sa famille allait mourir aux mains des fascistes : Son père de 77 ans Rafał, sa femme Hanna avec son fils de 10 ans Rafał et sa fille de 7 ans Narcyzka et d’autres habitants de la maison de la rue Wolska, se refugiant en vain dans la cave,. L’Insurrection fut écrasée, mais les représailles des Allemands ont continué et Varsovie a été brulé. Les restes calcinés de ses proches ont été retrouvés par Dariusz dans la cave sous les décombres de sa maison qu’en janvier 1945, après que les ruines de Varsovie aient été occupées par l’armée soviétique. Un soldat soviétique l’a laissé entrer dans la capitale encore hermétiquement fermée en échange d’un morceau de pain.

Il ne savait pas que quelques jours plus tard, le 6 août 1944, dans le Massacre de Wola, sa famille allait mourir aux mains des fascistes : Son père de 77 ans Rafał, sa femme Hanna avec son fils de 10 ans Rafał et sa fille de 7 ans Narcyzka et d’autres habitants de la maison de la rue Wolska, se refugiant en vain dans la cave,. L’Insurrection fut écrasée, mais les représailles des Allemands ont continué et Varsovie a été brulé. Les restes calcinés de ses proches ont été retrouvés par Dariusz dans la cave sous les décombres de sa maison qu’en janvier 1945, après que les ruines de Varsovie aient été occupées par l’armée soviétique. Un soldat soviétique l’a laissé entrer dans la capitale encore hermétiquement fermée en échange d’un morceau de pain.

![]() Hij wist niet dat een paar dagen later, op 6 augustus 1944, ’s morgens tijdens de ‘Slachting van Wola’, zijn familie uitgemoord werd door de fascisten: 77-jarige vader Rafał, vrouw Hanna samen met haar 10-jarige zoon Rafał en 7-jarige dochter Narcyza en anderen, die tevergeefs in de kelder schuilden, samen met andere bewoners van het huis in de Wolska-straat. De opstand viel, maar de vergelding van de Duitsers ging door en Warschau stond in brand. De verkoolde resten van zijn geliefden werden door Dariusz in de kelder gevonden onder de puin van zijn huis pas in januari 1945, nadat de ruïnes van Warschau door het Sovjetleger waren bezet. Hij werd in de nog steeds hermetisch afgesloten hoofdstad binnengelaten door een wachtdoende Sovjetsoldaat in ruil voor een stuk brood.

Hij wist niet dat een paar dagen later, op 6 augustus 1944, ’s morgens tijdens de ‘Slachting van Wola’, zijn familie uitgemoord werd door de fascisten: 77-jarige vader Rafał, vrouw Hanna samen met haar 10-jarige zoon Rafał en 7-jarige dochter Narcyza en anderen, die tevergeefs in de kelder schuilden, samen met andere bewoners van het huis in de Wolska-straat. De opstand viel, maar de vergelding van de Duitsers ging door en Warschau stond in brand. De verkoolde resten van zijn geliefden werden door Dariusz in de kelder gevonden onder de puin van zijn huis pas in januari 1945, nadat de ruïnes van Warschau door het Sovjetleger waren bezet. Hij werd in de nog steeds hermetisch afgesloten hoofdstad binnengelaten door een wachtdoende Sovjetsoldaat in ruil voor een stuk brood.

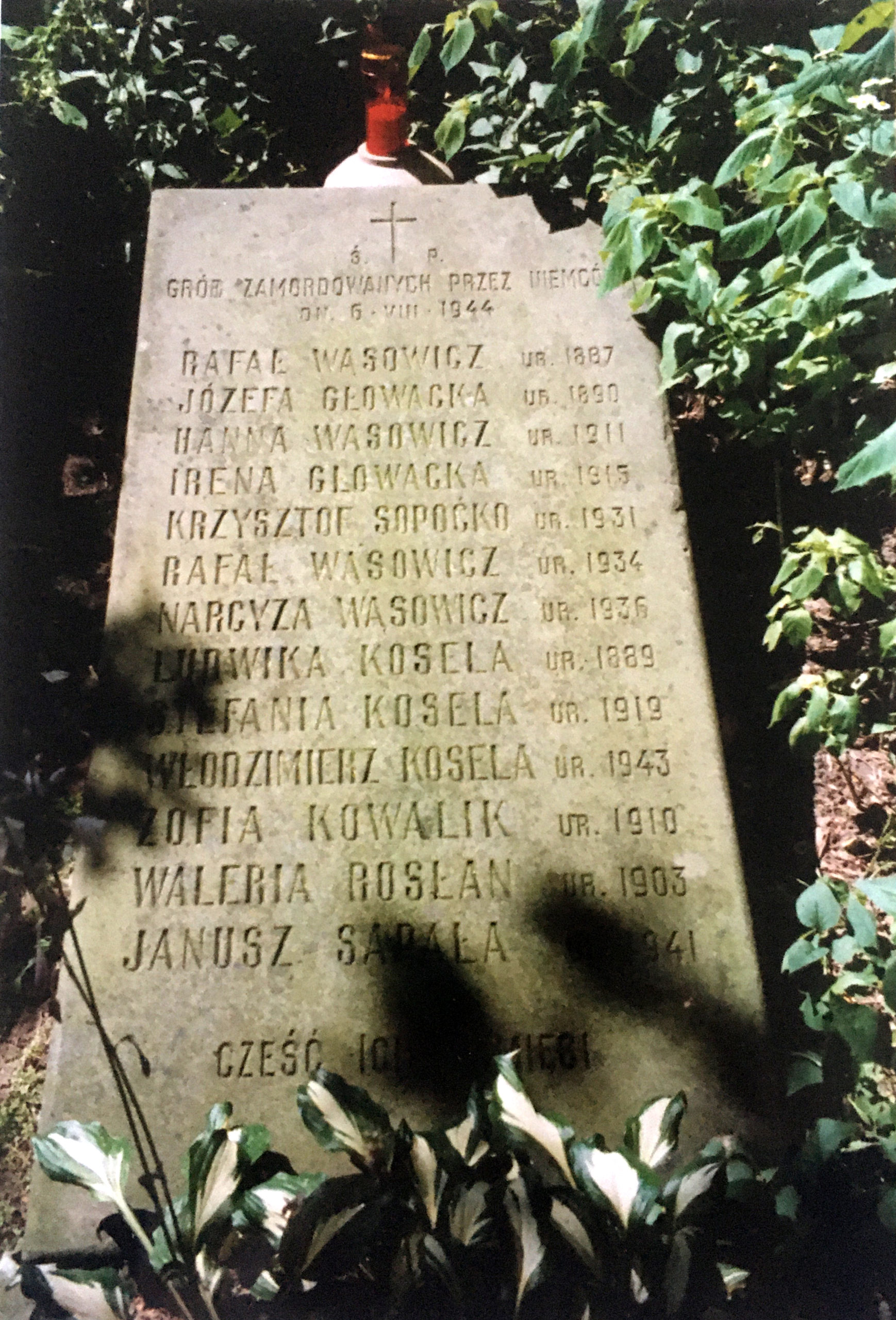

Ulica Wolska – Wolska street – Rue Wolska – Wolska straat – ca 1940

![]() Okoliczni mieszkańcy opowiadali, że 6 sierpnia 1944 z płonącej kamienicy Wąsowiczów unosił się wyjątkowo czarny dym. To paliła się pracownia malarska Rafała pełna obrazów olejnych oraz jego zbiory dzieł starych mistrzów miedzy innymi też malarzy holenderskich.Po Powstaniu Warszawskim została po tej kamienicy jedynie sterta gruzu a później wyrosło na tym terenie osiedle bloków mieszkalnych.

Okoliczni mieszkańcy opowiadali, że 6 sierpnia 1944 z płonącej kamienicy Wąsowiczów unosił się wyjątkowo czarny dym. To paliła się pracownia malarska Rafała pełna obrazów olejnych oraz jego zbiory dzieł starych mistrzów miedzy innymi też malarzy holenderskich.Po Powstaniu Warszawskim została po tej kamienicy jedynie sterta gruzu a później wyrosło na tym terenie osiedle bloków mieszkalnych.

![]() The surrounding residents who fled homes recalled that on August 6, 1944, exceptionally black smoke rose from the burning building of the Wąsowicz family. It was surely Rafał’s painting studio full of oil paintings and his collection of works by old masters, including Dutch painters.After the Warsaw Uprising, only a pile of rubble was left of this house and later an estate of blocks of flats rose in this area.

The surrounding residents who fled homes recalled that on August 6, 1944, exceptionally black smoke rose from the burning building of the Wąsowicz family. It was surely Rafał’s painting studio full of oil paintings and his collection of works by old masters, including Dutch painters.After the Warsaw Uprising, only a pile of rubble was left of this house and later an estate of blocks of flats rose in this area.

![]() Les habitants des environs ont raconté que le 6 août 1944, une fumée exceptionnellement noire planait depuis l’immeuble d’habitation en feu des Wąsowicz. C’était l’atelier de peinture de Rafał, rempli de peintures à l’huile et de sa collection d’œuvres de vieux maîtres, dont entre autres des peintres néerlandais. Après l’insurrection de Varsovie, il ne restait plus qu’un tas de décombres de cette maison et plus tard, un lotissement de blocs d’appartements s’est développé dans cette zone.

Les habitants des environs ont raconté que le 6 août 1944, une fumée exceptionnellement noire planait depuis l’immeuble d’habitation en feu des Wąsowicz. C’était l’atelier de peinture de Rafał, rempli de peintures à l’huile et de sa collection d’œuvres de vieux maîtres, dont entre autres des peintres néerlandais. Après l’insurrection de Varsovie, il ne restait plus qu’un tas de décombres de cette maison et plus tard, un lotissement de blocs d’appartements s’est développé dans cette zone.

![]() De vluchtende omwonenden vertelden dat op 6 augustus 1944 een uitzonderlijk zwarte rook omhoog steeg vanuit het brandend pand van de Wąsowicz’es. Het was vermoedelijk Rafał’s schildersatelier vol met olieverfschilderijen en zijn verzameling werken van oude meesters, waaronder Nederlandse schilders.Na de Opstand van Warschau bleef er van dit pand slechts een hoop puin over en later ontstond er op dit plek een woonwijk van flatgebouwen.

De vluchtende omwonenden vertelden dat op 6 augustus 1944 een uitzonderlijk zwarte rook omhoog steeg vanuit het brandend pand van de Wąsowicz’es. Het was vermoedelijk Rafał’s schildersatelier vol met olieverfschilderijen en zijn verzameling werken van oude meesters, waaronder Nederlandse schilders.Na de Opstand van Warschau bleef er van dit pand slechts een hoop puin over en later ontstond er op dit plek een woonwijk van flatgebouwen.

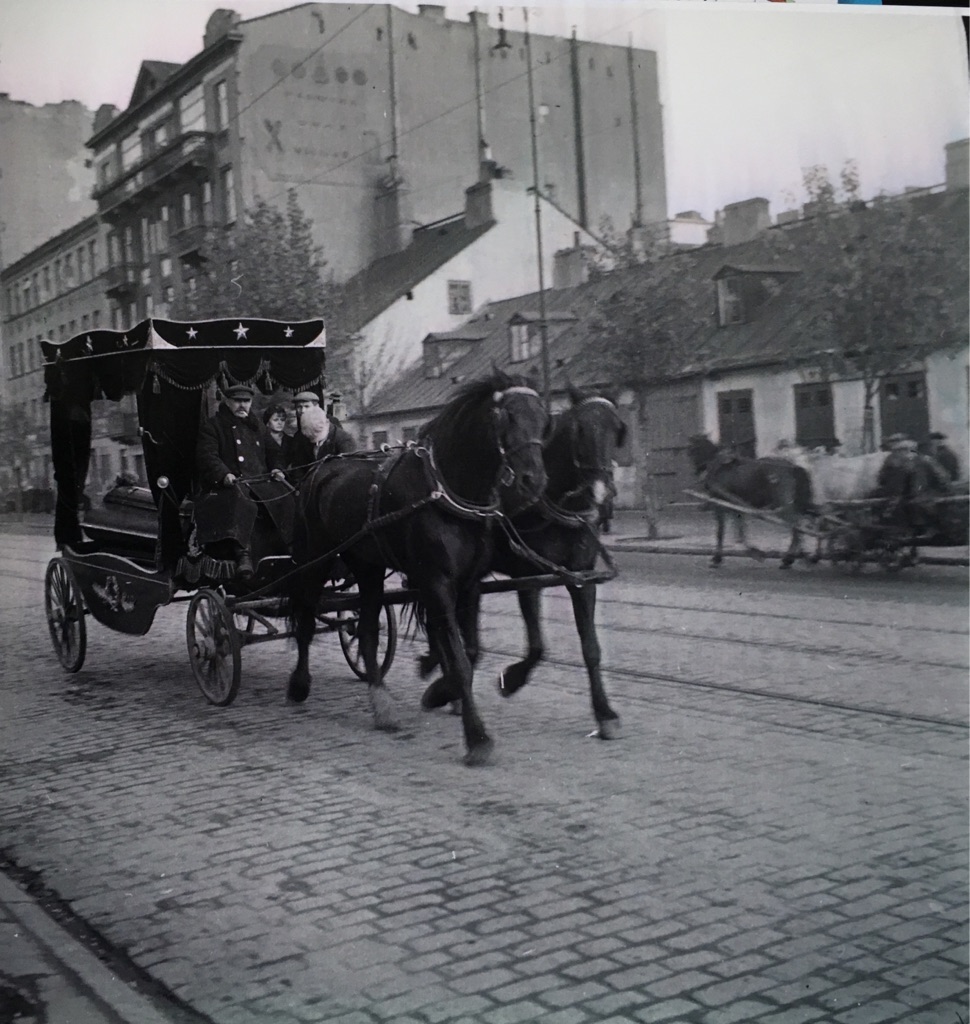

![]() Po upadku powstania Dariusz jak wielu uchodźców z Warszawy został przygarnięty przez dobrych ludzi pod Warszawą. Aby nie nadużywać ich gościnności postanowił, jak wielu innych bezdomnych Warszawiaków udać się do w miarę ocalałej Lodzi, prawie opustoszałej po wymordowaniu jej żydowskich mieszkańców. W drodze do Lodzi, na ciężarówce pełnej ocaleńców z Warszawy, młoda dziewczyna podarowała mu szczyptę tabaki do pustej fajki którą mechanicznie trzymał w ustach. Ta dziewczyna, Sabina, została później jego drugą żoną. Dzięki niej odnalazł chęć do życia. Podobno powiedział jej: ‘straciłem dwoje dzieci i chciałbym z Tobą mieć czworo’. Najstarsza Daria (dr Fizjologii Roślin po SGGW) urodziła się 30 maja 1946 roku, druga (ja) Gabryela w trzecią rocznicę Powstania 1 sierpnia 1947, Jacek (skrzypek) 2 czerwca 1950 i Blanka (fotograf ilustrator) 14 października 1951.

Po upadku powstania Dariusz jak wielu uchodźców z Warszawy został przygarnięty przez dobrych ludzi pod Warszawą. Aby nie nadużywać ich gościnności postanowił, jak wielu innych bezdomnych Warszawiaków udać się do w miarę ocalałej Lodzi, prawie opustoszałej po wymordowaniu jej żydowskich mieszkańców. W drodze do Lodzi, na ciężarówce pełnej ocaleńców z Warszawy, młoda dziewczyna podarowała mu szczyptę tabaki do pustej fajki którą mechanicznie trzymał w ustach. Ta dziewczyna, Sabina, została później jego drugą żoną. Dzięki niej odnalazł chęć do życia. Podobno powiedział jej: ‘straciłem dwoje dzieci i chciałbym z Tobą mieć czworo’. Najstarsza Daria (dr Fizjologii Roślin po SGGW) urodziła się 30 maja 1946 roku, druga (ja) Gabryela w trzecią rocznicę Powstania 1 sierpnia 1947, Jacek (skrzypek) 2 czerwca 1950 i Blanka (fotograf ilustrator) 14 października 1951.

![]() After the fall of the uprising, Dariusz, like many refugees from Warsaw, was taken in by good people near Warsaw. In order not to abuse their hospitality, he decided, like many other homeless Warsaw residents, to go to the fairly undamaged city of Lodz, almost deserted after the extinction of its Jewish inhabitants. On the way to Lodz, on a truck full of survivors from Warsaw, a young girl offered him a pinch of snuff for the empty pipe which he mechanically held in his mouth. This girl, Sabina, later became his second wife. Thanks to her, he regained the desire to live. Apparently, he told her: “I lost two children and I’d like to have four with you. The eldest Daria (PhD in Plant Physiology after SGGW) was born on 30 May 1946, the second (me) Gabryela on the 1st of August 1947, the third anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising , Jacek (violinist) on 2nd of June 1950 and Blanka (photographer illustrator) on 14th of October 1951.

After the fall of the uprising, Dariusz, like many refugees from Warsaw, was taken in by good people near Warsaw. In order not to abuse their hospitality, he decided, like many other homeless Warsaw residents, to go to the fairly undamaged city of Lodz, almost deserted after the extinction of its Jewish inhabitants. On the way to Lodz, on a truck full of survivors from Warsaw, a young girl offered him a pinch of snuff for the empty pipe which he mechanically held in his mouth. This girl, Sabina, later became his second wife. Thanks to her, he regained the desire to live. Apparently, he told her: “I lost two children and I’d like to have four with you. The eldest Daria (PhD in Plant Physiology after SGGW) was born on 30 May 1946, the second (me) Gabryela on the 1st of August 1947, the third anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising , Jacek (violinist) on 2nd of June 1950 and Blanka (photographer illustrator) on 14th of October 1951.

![]() Après la chute de ‘l’Insurrection’, Dariusz, comme de nombreux réfugiés de Varsovie, a été recueilli par de braves gens près de Varsovie. Afin de ne pas abuser de leur hospitalité, il a décidé, comme beaucoup d’autres habitants de Varsovie sans abri, de se rendre dans la ville de Lodz assez bien conservée et presque déserte après le meurtre de ses habitants juifs. Sur le chemin de Lodz, dans un camion rempli de survivants de Varsovie, une jeune fille lui a offert une pincée de tabac pour la pipe vide qu’il tenait mécaniquement dans sa bouche. Cette fille, Sabina, est devenue plus tard sa seconde épouse. Grâce à elle, il a retrouvé le désir de vivre. Apparemment, il lui a dit : “J’ai perdu deux enfants et j’aimerais en avoir quatre avec vous. L’aînée Daria (docteur en physiologie des plantes après SGGW) est née le 30 mai 1946, la seconde (moi) Gabryela le 1er août 1947, lors du troisième anniversaire de ‘l’Insurrection’ de Varsovie, Jacek (violoniste) le 2 juin 1950 et Blanka (photographe illustrateur) le 14 octobre 1951.

Après la chute de ‘l’Insurrection’, Dariusz, comme de nombreux réfugiés de Varsovie, a été recueilli par de braves gens près de Varsovie. Afin de ne pas abuser de leur hospitalité, il a décidé, comme beaucoup d’autres habitants de Varsovie sans abri, de se rendre dans la ville de Lodz assez bien conservée et presque déserte après le meurtre de ses habitants juifs. Sur le chemin de Lodz, dans un camion rempli de survivants de Varsovie, une jeune fille lui a offert une pincée de tabac pour la pipe vide qu’il tenait mécaniquement dans sa bouche. Cette fille, Sabina, est devenue plus tard sa seconde épouse. Grâce à elle, il a retrouvé le désir de vivre. Apparemment, il lui a dit : “J’ai perdu deux enfants et j’aimerais en avoir quatre avec vous. L’aînée Daria (docteur en physiologie des plantes après SGGW) est née le 30 mai 1946, la seconde (moi) Gabryela le 1er août 1947, lors du troisième anniversaire de ‘l’Insurrection’ de Varsovie, Jacek (violoniste) le 2 juin 1950 et Blanka (photographe illustrateur) le 14 octobre 1951.

![]() Na de val van de opstand werd Dariusz, zoals veel vluchtelingen uit Warschau, opgevangen door goede mensen in de buurt van Warschau. Om geen misbruik te maken van hun gastvrijheid besloot hij, net als veel andere dakloze inwoners van Warschau, om naar de redelijk onbeschadigd stad Lodz te gaan, die na het uitroeien van de Joodse inwoners bijna verlaten was. Op weg naar Lodz, op een vrachtwagen vol overlevenden uit Warschau, gaf een jonge vrouw hem een snuifje snuiftabak voor de lege pijp die hij mechanisch in zijn mond hield. Deze jonge vrouw, Sabina, werd later zijn tweede vrouw. Dankzij haar hervond hij zin om te leven. Blijkbaar heeft hij haar verteld: “Ik heb twee kinderen verloren en ik wil graag vier met jou hebben. De oudste Daria (doctor in de plantenfysiologie na SGGW) werd geboren op 30 mei 1946, de tweede (ik) Gabryela op 1 augustus 1947, de derde verjaardag van de Warschauopstand, Jacek (violist) op 2 juni 1950 en Blanka (fotograaf-illustrator) op 14 oktober 1951.

Na de val van de opstand werd Dariusz, zoals veel vluchtelingen uit Warschau, opgevangen door goede mensen in de buurt van Warschau. Om geen misbruik te maken van hun gastvrijheid besloot hij, net als veel andere dakloze inwoners van Warschau, om naar de redelijk onbeschadigd stad Lodz te gaan, die na het uitroeien van de Joodse inwoners bijna verlaten was. Op weg naar Lodz, op een vrachtwagen vol overlevenden uit Warschau, gaf een jonge vrouw hem een snuifje snuiftabak voor de lege pijp die hij mechanisch in zijn mond hield. Deze jonge vrouw, Sabina, werd later zijn tweede vrouw. Dankzij haar hervond hij zin om te leven. Blijkbaar heeft hij haar verteld: “Ik heb twee kinderen verloren en ik wil graag vier met jou hebben. De oudste Daria (doctor in de plantenfysiologie na SGGW) werd geboren op 30 mei 1946, de tweede (ik) Gabryela op 1 augustus 1947, de derde verjaardag van de Warschauopstand, Jacek (violist) op 2 juni 1950 en Blanka (fotograaf-illustrator) op 14 oktober 1951.

Ojczulek – Zakopane (1950’s)

Ojczulek i Sabina -Warsaw ca 1970

![]() Po wojnie Ojczulek postanowił wybrać wolny zawód artysty malarza. Malował głównie pejzaż polski i wedutę warszawską. Obok technik malarskich: olejnej i akwareli uprawiał też grafikę artystyczną. Był członkiem Polskiego Związku Artystów Plastyków. Przez kilka lat prowadził pracownię graficzną w Warszawie i kilkakrotnie był komisarzem popularnej dorocznej subskrypcji grafiki artystycznej. Stymulował też w nas wybór kierunków artystycznych argumentując to niezależnością, od takich czy innych autorytetów czy systemów politycznych, jaką oferuje wolny zawód artysty. Polacy mają wrodzony szacunek dla sztuki, kultury i artystów. Dlatego zawsze z lekką dumą wypełniałam na formularzach – zawód ojca – artysta malarz.

Po wojnie Ojczulek postanowił wybrać wolny zawód artysty malarza. Malował głównie pejzaż polski i wedutę warszawską. Obok technik malarskich: olejnej i akwareli uprawiał też grafikę artystyczną. Był członkiem Polskiego Związku Artystów Plastyków. Przez kilka lat prowadził pracownię graficzną w Warszawie i kilkakrotnie był komisarzem popularnej dorocznej subskrypcji grafiki artystycznej. Stymulował też w nas wybór kierunków artystycznych argumentując to niezależnością, od takich czy innych autorytetów czy systemów politycznych, jaką oferuje wolny zawód artysty. Polacy mają wrodzony szacunek dla sztuki, kultury i artystów. Dlatego zawsze z lekką dumą wypełniałam na formularzach – zawód ojca – artysta malarz.

![]() After the war, Ojczulek decided to continue the free profession of an artist-painter. He painted mainly Polish landscapes and the Warsaw veduta. Apart from painting techniques: oil and watercolor, he also practiced artistic graphics. He was a member of the Polish Association of Visual Artists. For a few years he led a graphic design studio in Warsaw and several times he was a commissioner of the popular annual subscription of artistic graphics. He also stimulated our choice of artistic directions, arguing that these were independent, from such or other authorities or political systems as free artist’s professions offer. Poles have innate respect for art, culture and artists. That is why I have always filled in the forms – father’s profession ‘artist painter’ with a little pride.

After the war, Ojczulek decided to continue the free profession of an artist-painter. He painted mainly Polish landscapes and the Warsaw veduta. Apart from painting techniques: oil and watercolor, he also practiced artistic graphics. He was a member of the Polish Association of Visual Artists. For a few years he led a graphic design studio in Warsaw and several times he was a commissioner of the popular annual subscription of artistic graphics. He also stimulated our choice of artistic directions, arguing that these were independent, from such or other authorities or political systems as free artist’s professions offer. Poles have innate respect for art, culture and artists. That is why I have always filled in the forms – father’s profession ‘artist painter’ with a little pride.

![]() Après la guerre, Ojczulek a décidé de choisir la profession libre d’artiste-peintre. Il a peint principalement des paysages polonais et la veduta de Varsovie. Outre les techniques de peinture : huile et aquarelle, il pratique également le graphisme artistique. Il était membre de l’Association polonaise des artistes de beaux-arts. Pendant quelques années, il a dirigé un studio de gravure à Varsovie et, à plusieurs reprises, il a été le commissaire d’une exposition annuelle populaire de gravure artistique. Il a également stimulé notre choix d’études en directions artistiques, arguant qu’ils étaient indépendants, de telles ou d’autres autorités ou systèmes politiques comme le propose la profession d’artiste indépendant. Les Polonais ont un respect inné pour l’art, la culture et les artistes. C’est pourquoi j’ai toujours rempli, avec un peu de fierté, le métier de père ‘artiste-peintre’ dans les formulaires.

Après la guerre, Ojczulek a décidé de choisir la profession libre d’artiste-peintre. Il a peint principalement des paysages polonais et la veduta de Varsovie. Outre les techniques de peinture : huile et aquarelle, il pratique également le graphisme artistique. Il était membre de l’Association polonaise des artistes de beaux-arts. Pendant quelques années, il a dirigé un studio de gravure à Varsovie et, à plusieurs reprises, il a été le commissaire d’une exposition annuelle populaire de gravure artistique. Il a également stimulé notre choix d’études en directions artistiques, arguant qu’ils étaient indépendants, de telles ou d’autres autorités ou systèmes politiques comme le propose la profession d’artiste indépendant. Les Polonais ont un respect inné pour l’art, la culture et les artistes. C’est pourquoi j’ai toujours rempli, avec un peu de fierté, le métier de père ‘artiste-peintre’ dans les formulaires.

![]() Na de oorlog besloot Ojczulek het vrij beroep van kunstschilder te verkiezen. Hij schilderde vooral Poolse landschappen en de Warschause veduta. Naast de schildertechnieken: olieverf en aquarel, beoefende hij ook artistieke-grafiek. Hij was lid van de Poolse Vereniging van Beeldende Kunstenaars. Een paar jaar lang leidde hij een grafisch atelier in Warschau en verschillende keren was hij commissaris van het populaire jaartentoonstelling van artistieke grafiek. Hij stimuleerde ook onze keuze van artistieke studierichtingen, met het argument dat het vrije kunstenaarsberoep onafhankelijkheid bood, van deze of andere autoriteiten of politieke systemen. De Polen hebben een aangeboren respect voor kunst, cultuur en kunstenaars. Daarom heb ik in de formulieren onder, het beroep van vader, altijd met een beetje trots ingevuld ‘kunstschilder’.

Na de oorlog besloot Ojczulek het vrij beroep van kunstschilder te verkiezen. Hij schilderde vooral Poolse landschappen en de Warschause veduta. Naast de schildertechnieken: olieverf en aquarel, beoefende hij ook artistieke-grafiek. Hij was lid van de Poolse Vereniging van Beeldende Kunstenaars. Een paar jaar lang leidde hij een grafisch atelier in Warschau en verschillende keren was hij commissaris van het populaire jaartentoonstelling van artistieke grafiek. Hij stimuleerde ook onze keuze van artistieke studierichtingen, met het argument dat het vrije kunstenaarsberoep onafhankelijkheid bood, van deze of andere autoriteiten of politieke systemen. De Polen hebben een aangeboren respect voor kunst, cultuur en kunstenaars. Daarom heb ik in de formulieren onder, het beroep van vader, altijd met een beetje trots ingevuld ‘kunstschilder’.

Dariusz Wąsowicz , Warsaw-Old Town, oil on canvas

![]() Do tej pory pamiętam sylwetkę Ojczulka przy sztalugach, zarysowującą się pod światło wpadające przez okno, kiedy rano jeszcze w piżamie wchodziłam do pokoju gdzie najwyraźniej już od paru godzin siedział zatopiony w pracy.

Do tej pory pamiętam sylwetkę Ojczulka przy sztalugach, zarysowującą się pod światło wpadające przez okno, kiedy rano jeszcze w piżamie wchodziłam do pokoju gdzie najwyraźniej już od paru godzin siedział zatopiony w pracy.

![]() Still now I remember Ojczulek’s silhouette against the light falling through the window, seated at his painting easel, when in the morning still in my pajamas I entered the room where he had apparently been sunk at work for hours.

Still now I remember Ojczulek’s silhouette against the light falling through the window, seated at his painting easel, when in the morning still in my pajamas I entered the room where he had apparently been sunk at work for hours.

![]() Jusqu’à présent, je me souviens de la silhouette de mon père devant son chevalet, vu en contre jour de la lumière tombante par la fenêtre, alors que encore en pyjama le matin j’entrais dans la pièce où il était apparemment submergé de travail pendant des heures.

Jusqu’à présent, je me souviens de la silhouette de mon père devant son chevalet, vu en contre jour de la lumière tombante par la fenêtre, alors que encore en pyjama le matin j’entrais dans la pièce où il était apparemment submergé de travail pendant des heures.

![]() Nog steeds herinner ik me Ojczulek’s silhouet achter zijn schildersezel, tegen het licht dat door het raam viel, toen ik ’s morgens nog in mijn pyjama de kamer binnenkwam waar hij blijkbaar al urenlang verzonken in het werk had gezeten.

Nog steeds herinner ik me Ojczulek’s silhouet achter zijn schildersezel, tegen het licht dat door het raam viel, toen ik ’s morgens nog in mijn pyjama de kamer binnenkwam waar hij blijkbaar al urenlang verzonken in het werk had gezeten.

![]() Ojczulek był człowiekiem, który dał się lubić. Lubiła go też bywająca u nas w domu gromada naszych rówieśników, kolegów ze szkoły i ze studiów. Niejedni z nich przypominają sobie jeszcze długie zabawne wiersze pełne aktualności, które pisywał na początek i koniec roku szkolnego lub inne szkolne okazje. Ojczulek zmarł w Warszawie 14 marca 1973 w wieku 63 lat, po trzech zawałach serca. Koledzy Jacka z konserwatorium wzruszająco grali Ojczulkowi na pogrzebie Andante cantabile z Kwartetu smyczkowego zwanego ‘Dysonansowym’ Mozarta. W tej chwili staram się zadbać o spuściznę malarską Ojczulka. Po oczyszczeniu i restauracji obrazów, które pozostały w mieszkaniu na Puławskiej zamierzam zorganizować wystawę pośmiertną we współpracy z galerią Katarzyny Napiórkowskiej. Kiedy to się uda, jeszcze nie wiem.

Ojczulek był człowiekiem, który dał się lubić. Lubiła go też bywająca u nas w domu gromada naszych rówieśników, kolegów ze szkoły i ze studiów. Niejedni z nich przypominają sobie jeszcze długie zabawne wiersze pełne aktualności, które pisywał na początek i koniec roku szkolnego lub inne szkolne okazje. Ojczulek zmarł w Warszawie 14 marca 1973 w wieku 63 lat, po trzech zawałach serca. Koledzy Jacka z konserwatorium wzruszająco grali Ojczulkowi na pogrzebie Andante cantabile z Kwartetu smyczkowego zwanego ‘Dysonansowym’ Mozarta. W tej chwili staram się zadbać o spuściznę malarską Ojczulka. Po oczyszczeniu i restauracji obrazów, które pozostały w mieszkaniu na Puławskiej zamierzam zorganizować wystawę pośmiertną we współpracy z galerią Katarzyny Napiórkowskiej. Kiedy to się uda, jeszcze nie wiem.

![]() Ojczulek was a likeable person. He was also liked by our friends, colleagues from school and university. Many of them still remember the long funny poems full of news which he wrote for the beginning and end of the school year or other school occasions. Ojczulek died in Warsaw on March 14th, 1973 at the age of 63, after three heart attacks. Jacek’s friends from the Conservatory touchingly played at Ojczulek’s funeral the Andante Cantabile from Mozart’s Dissonance String Quartet. I am now trying to take care of Ojczulek’s painting legacy. After cleaning and restoring the paintings that remained in the apartment on Puławska Street, I intend to organize a posthumous exhibition in cooperation with Katarzyna Napiórkowska’s gallery. When it will be possible, I do not know yet.

Ojczulek was a likeable person. He was also liked by our friends, colleagues from school and university. Many of them still remember the long funny poems full of news which he wrote for the beginning and end of the school year or other school occasions. Ojczulek died in Warsaw on March 14th, 1973 at the age of 63, after three heart attacks. Jacek’s friends from the Conservatory touchingly played at Ojczulek’s funeral the Andante Cantabile from Mozart’s Dissonance String Quartet. I am now trying to take care of Ojczulek’s painting legacy. After cleaning and restoring the paintings that remained in the apartment on Puławska Street, I intend to organize a posthumous exhibition in cooperation with Katarzyna Napiórkowska’s gallery. When it will be possible, I do not know yet.

![]() Ojczulek était un homme aimable. Il était également aimé par un groupe de nos pairs, des collègues de l’école et de l’université. Beaucoup d’entre eux se souviennent encore des longs poèmes drôles et pleins d’actualités qu’il écrivait pour le début et à la fin de l’année scolaire ou à d’autres occasions. Ojczulek est décédé à Varsovie le 14 mars 1973 à l’âge de 63 ans, après trois crises cardiaques. Aux funérailles de Ojczulek des amis de Jacek du Conservatoire ont joué émus l’Andante cantabile du quatuor à cordes appelé “Dissonances” de Mozart. A présent j’essaie de m’occuper de l’héritage de peinture d’Ojczulek. Après avoir fair nettoyé et restauré les peintures qui sont restées dans l’appartement de la rue Puławska, j’ai l’intention d’organiser une exposition posthume en coopération avec la galerie de Katarzyna Napiórkowska à Varsovie. Je ne sais pas encore quand cela se réalisera.

Ojczulek était un homme aimable. Il était également aimé par un groupe de nos pairs, des collègues de l’école et de l’université. Beaucoup d’entre eux se souviennent encore des longs poèmes drôles et pleins d’actualités qu’il écrivait pour le début et à la fin de l’année scolaire ou à d’autres occasions. Ojczulek est décédé à Varsovie le 14 mars 1973 à l’âge de 63 ans, après trois crises cardiaques. Aux funérailles de Ojczulek des amis de Jacek du Conservatoire ont joué émus l’Andante cantabile du quatuor à cordes appelé “Dissonances” de Mozart. A présent j’essaie de m’occuper de l’héritage de peinture d’Ojczulek. Après avoir fair nettoyé et restauré les peintures qui sont restées dans l’appartement de la rue Puławska, j’ai l’intention d’organiser une exposition posthume en coopération avec la galerie de Katarzyna Napiórkowska à Varsovie. Je ne sais pas encore quand cela se réalisera.